And he [Abraham] lifted up his eyes and looked, and, lo, three men stood over against him… (Genesis 18:2)

On this blog, we often discuss the collapse of the wavefunction as the result of a measurement. This phenomenon is called the “measurement problem.” There are several reasons, for which the collapse of the wavefunction—part and parcel of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics—is considered a problem. Firstly, it does not follow from the Schrödinger equation, the main equation of quantum mechanics that describes the evolution of the wavefunction in time, and is added ad hoc. Second, nobody knows how the collapse happens or how long the wave function takes to collapse. This is not even to consider that any notion that the collapse of the wavefunction is caused by human consciousness, as proposed by Von Neumann, leading to Cartesian dualism, is anathema to physicists. It is a problem, no matter how you look at it. What is the solution? The most radical, but the most accepted solution is the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Proposed by Hugh Everett in 1957 (H. Everett, Review of Modern Physics, July 1957) and developed by Bryce de Witt, (B. S. DeWitt and N. Graham, The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton Univ. Press, 1974) the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is, perhaps, the most outlandish yet the cleanest interpretation of the Schrödinger equation. This theory suggests that every transition between quantum states splits the universe into multiple copies or “branches,” in which all of the possible states are realized.

This approach, as weird as it sounds—Bryce DeWitt called it “schizophrenia with vengeance”—is actually the most straightforward interpretation of the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics because it does not rely on an ad hoc collapse of the wavefunction. Recall that the Schrödinger equation does not describe the evolution of a physical system per se, but the evolution in time of the wavefunction describing the state of the system.

Max Born interpreted the wavefunction as the measure of the probability of finding the system in a particular state. More precisely, the squared amplitude of the wavefunction is the probability of finding the system in a certain region of the configurational space. Thus we cannot say anything certain about finding the system in any particular state. We can only speak of probabilities of finding the system in a particular state or place. However, when we measure the parameters of the system, such as its position or momentum, we always get a particular value of the parameter we measure. It is as if the cloud of probabilities has suddenly collapsed to a single point – the value we find in an experiment. Hence, the measurement problem. Instead, Everett suggested that no collapse takes place. Instead, all possible states are realized in different universes. Every time-irreversible event – be that a transition between quantum-mechanical states or the measurement – splits the world into as many branches as there are possible outcomes, which are all realized in respective branches of the universe.

On this level, parallel universes remain an optional interpretation of quantum mechanics, which has its followers and its skeptics. On the level of quantum cosmology, however, we are almost compelled to adopt this interpretation. Indeed, in the quantum cosmology described by the Wheeler-DeWitt equation, the universal wavefunction Ψ(h, F, S) is defined on an ensemble of all possible space-like universes, and is interpreted as a probability amplitude to find a particular manifold S with a particular geometry h and non-gravitational fields F. The Anthropic principle is usually invoked to select that universe, which allows for the emergence of life and intelligent beings that are capable of asking the question: which particular universe we live in.

It is remarkable that the many-worlds interpretation or parallel universes idea boasts among its supporters such luminaries as Richard Feynman, Steven Hawking, Murray Gell-Mann, Steven Weinberg, and some of the other best theoretical physicists of the twentieth century.

The classical Jewish sources are replete with the notion of multiple worlds and parallel universes. Consider, for example, the universes of Tohu (Chaos) and Tikkun (Rectification) that coexist parallel to each other. Or the four worlds of ABYA: Atzilut (the world of Splendor), Briyah (the world of Creation), Yetzirah (the world of Formation) and Assiya (the world of Action), each of which is said to be subdivided into a myriad of parallel worlds. Needless to say, all these “universes” denote spiritual rather than physical worlds.

The most troubling aspect of the many-worlds approach is that it suggests that the observer also splits into multiple copies completely oblivious of each other – “schizophrenia with a vengeance!”

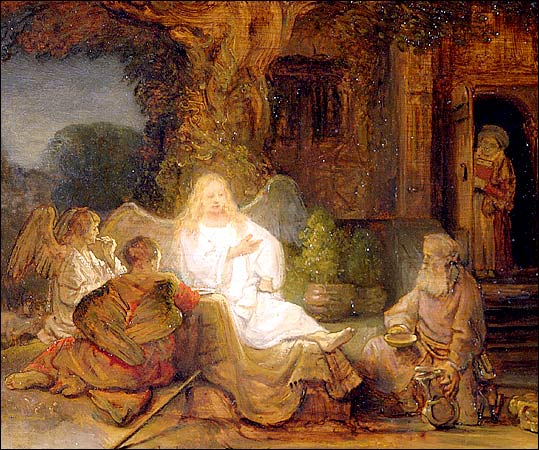

Let us look into this week’s Torah portion – Vayera. The second verse says:

And he [Abraham] lifted up his eyes and looked, and, lo, three men stood over against him… (Genesis 18:2)

The Zohar suggests that the three persons who came to visit Abraham in Mamre were no other than Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Here we have a “celestial copy” of Abraham visiting the “terrestrial copy” of Abraham, the two coexisting in parallel universes.

This idea is further stressed by the way we read the Torah scroll. According to the Mesorah, the Jewish Rabbinical tradition, the Torah scroll is read using cantillation marks (taamey ha-miqra or “trope”) that one can find in Tikun Sofrim or in most printed editions of the Chumash (Pentateuch). Later in this Torah portion, in the story of the binding of Isaac, the Akeida, an angel called to Abraham from heaven and said,

Abraham! Abraham! (Genesis 22:11).

There is a vertical line (a cantillation mark) between the first Abraham and the repetition of the name: “Abraham | Abraham.” This sign tells the reader to pause between the first Abraham and the second Abraham when reading the Torah scroll. The Kabbalah and Chassidic philosophy (see, for example, Hemshech Samech Vav by Rabbi Dovber of Lubavitch) explain that the pause is required to distinguish between the celestial Abraham and the terrestrial Abraham.

In this Torah portion, Vayera, at least in the Zohar’s interpretation, we read about the terrestrial Abraham meeting his celestial counterpart. This situation is analogous to the parallel universe interpretation of quantum mechanics, which allows for the occasional merger of the parallel universes. Indeed, it is as if the spiritual universe – the abode of the celestial Abraham – merged for a moment with the physical universe – the abode of the terrestrial Abraham – to allow for their face-to-face encounter.

Biblical commentators struggle to explain the meaning of the language used by the Torah in the last week’s portion Lech Lecha, when G‑d tells Abram “lech lecha,” lit. go to yourself. Seemingly, it does not make sense in a literal translation. Some translators simply read out “to yourself” part, others translate it as “for your own good,” which is far from the literal meaning. Given our explanation above, perhaps it simply means a commandment for Abram to go to himself – his higher self, his celestial counterpart, with whom he ultimately meets in this Torah portion, Vayera.

Each Jew, a descendant of Abraham, has a celestial counterpart, the higher self – it is called the G‑dly soul – nefesh Elokit. When Abram was told by G‑d to leave his land and his father’s house and go to his higher self, Abram was not a Jew yet – this was before the covenant G‑d made with him, before he was given a new name – Abraham. He only merited to meet his higher self after his circumcision, after he became the first Jew. Children of Abraham, the Jewish people, have their higher self, their G‑dly soul, inside. As the Tanya says, every Jew possesses nefesh Elokit, which is helek Eloka memaal mamash – “a part of G‑d from above indeed.” Thus, our task is not going outside ourselves to seek our higher self, as our forefather Abraham had to do but to direct our attention inward, to return to our true G‑dly self. That is why the word teshuvah should not be translated as “repentance” but as “return,” which is what it literally means – return to our higher self. Our father Abraham paved the way for us.

Thank you, Alex. Gut voch.

Amazing, a big yashar koach!

Thank you, Alex. It is very interesting. Sorry for being late in reading and commenting on your article.

I have a couple of thoughts:

Among the multitude of all “possible” parallel universes you select only two – celestial and terrestrial – to explain textual ambiguity. Would it not be simpler to invoke “prohibited” Cartesian dualism for the textual explanations? I think everything will then fall into place.

Also, what are your thoughts about the Multiverse interpretation by David Deutsch?

On the one hand, Rashi says the three visitors were angels. On the other, the Zohar says they were Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Angels live in the celestial sphere. Consequently, the only conclusion possible two reconcile both opinions is to assume that terrestrial Abraham met his celestial counterpart. The Occam’s Razor principle requires the most economical explanation drawing on the fewest assumptions. I don’t see any need to bring multiple other universes into this account when two are sufficient for our purposes.

The Cartesian dualism speaks of the mind-body dualism. The visitors that came to Abraham had a physical appearance and were not fruits of Abraham’s imagination. He was not hallucinating. I don’t how Cartesian dualism fits into this picture.

Alex, you are right applying The Occam’s Razor principle in this situation – two Universes are plenty for two Abrahams. My understanding of celestial is “heavenly” (being in the mind), while terrestrial is “earthy” (being in the body), that is why I suggested Cartesian dualism. Perhaps, I am wrong, and both Abrahams, as you insist, were real and they were not hallucinating.

Then in which Universe did they meet, the first, the second, or even in the third, because of short-lived merger? How did this encounter effect all those Universes and their Abrahams now having knowledge about the encounter?

The celestial universe is indeed “heavenly,” but it doesn’t mean it’s in your mind. In this case, “heavenly” or “celestial” simply means spiritual. The word “spiritual” does not have a precise definition in the scientific vocabulary except for meaning “not-physical.” However, one Kabbalah, spiritual world means a world that has no spatial limitations. I can easily define it as a world of higher dimensions. Say, we consider a ten-dimensional universe, in which the first three dimensions are familiar to us spatial dimensions. I would call the remaining seven dimensions a “spiritual” part of this universe, because this is a part not limited by our spatial limitations. But this is another topic.

The terrestrial Abraham met his celestial counterpart in this physical (terrestrial) world. In Everett’s many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, the branches of the universe, after they split, never meet again. However, in a closely related but slightly different interpretation, called parallel universes interpretation, wherein the universe does not split but exists ab initio in multiple strata (i.e., parallel universes) with the wavefunction apportioned among these strata, the parallel universes can merge through the process of superposition.

Ok, we can say even 11 dimensions as the latest String Theory suggests, but after the encounter of Abrahams the whole strata will not be the same as before the encounter, meaning the previous probabilities for each participating Universe (as square of the amplitude of the wavefunction) will be different. And in which Universe are we communicating now – with the first Abraham, the second, or the merged? Yes, it is crazy.

Also, I still would like to hear your opinion about the Multiverse interpretation by David Deutsch, if you are familiar with it. To me it is the latest and the most amazing development of Hugh Everett’s ideas. Thank you.