In the first installment of the Standard Model,[1] we uncovered a curious parallel between the arrangement of the elementary particles in the Standard Model (a.k.a. quantum field theory) and Seder Hishtalshelut—the chainlike ontological order of creation—a central doctrine of the Lurianic Kabbalah.[2] In this third installment, we will discover how the proper name of G‑d, the Tetragrammaton, is hard-wired in the standard model.

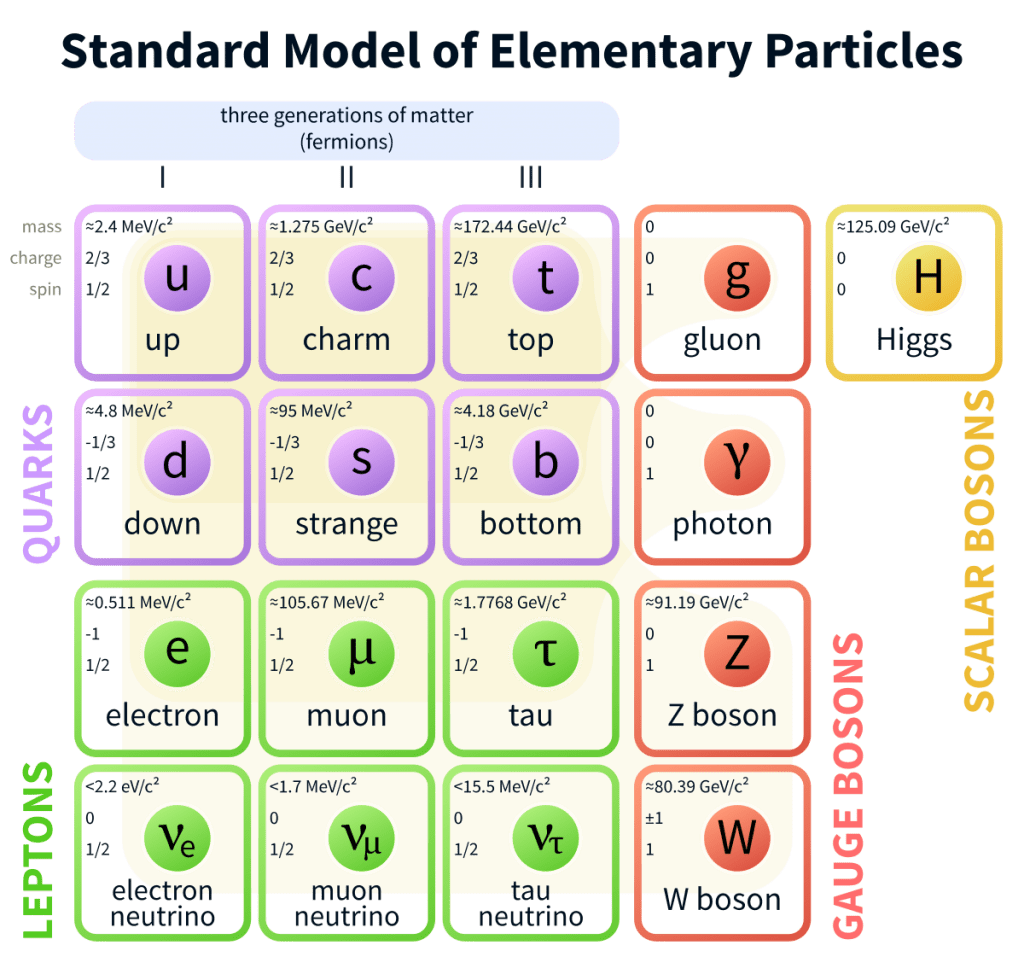

In the Standard Model, all elementary particles are arranged in a four-by-four grid (with the addition of the Higgs Boson in some representations).[3] It is axiomatic in the Kabbalah that all things that are four are rooted in the four letters of the Tetragrammaton: yud (Y), heh (H), waw (W), and heh (H). In the first installment of the Standard Model, we showed that all elementary particles of the Standard Model nicely line up in a four-by-four grid where the columns correspond to the four worlds of Seder Hishtalshelut, and the rows correspond to arba yesodot (“four foundations” a.k.a. “four elements”). Let us recall now that four words and four elements correspond to four letters of the Tetragrammaton (Y-H-W-H), as stated there.[4]

Having already established a connection between the Standard Model of elementary particles and the Tetragrammaton (shem Havayah), we can explore this parallel further.

There are different ways of counting elementary particles. These variations are based on various flavors of the bosons—the quanta of fundamental forces. For example, there are eight flavors of gluons—the quantum of the strong nuclear force. Do we count them as one particle or eight? Two types of bosons carry weak nuclear force—W boson and Z boson. Do we count them as one or two distinct particles? These variations in the taxonomy of elementary particles are not fundamental and only affect how they are presented graphically on a grid. However, each such presentation can be metaphorically related to the Tetragrammaton.

Sixteen Particles

In the most straightforward representation, where carriers of each field are considered as a single particle regardless of their various flavors, gives us sixteen elementary particles:[5]

Fermions (matter particles):

- Quarks: Up, Down, Charm, Strange, Top, Bottom (six particles);

- Leptons: Electron, Electron neutrino, Muon, Muon neutrino, Tau, Tau neutrino (six particles);

Bosons (four force-carrying particles):

- Photon (electromagnetic force);

- W and Z bosons (weak nuclear force);

- Gluons (strong nuclear force);

- Higgs Boson (associated with the Higgs field, responsible for the mass of other particles).

These sixteen particles neatly fit into a four-by-four grid representation:

| Y-H-W-H | Yud | Heh | Waw | Heh |

| Yud | Up Quark (u) | Charm Quark (c) | Top Quark (t) | Photons (γ) |

| Heh | Down Quark (d) | Strange Quark (s) | Bottom Quark (b) | Gluons (g) |

| Waw | Electron (e) | Muon (µ) | Tau (τ) | W Boson (W) Z Bosons (Z) |

| Heh | Electron Neutrino (νe) | Muon Neutrino (νµ) | Tau Neutrino (ντ) | Higgs Boson (H) |

It is axiomatic in Kabbalah that everything is interincluded in a fractal fashion. This is why the four worlds—Aẓilut, Beriyah, Yeẓirah, and Asiyah—are each further subdivided into four subworlds Aẓilut of Aẓilut, Beriyah of Aẓilut, Yeẓirah of Aẓilut, etc., filling out a four-by-four grid, as above. The parallel is clear: the sixteen elementary particles of the Standard Model parallel sixteen combinations of the four letters of the Tetragrammaton.

Twenty-four Particles

When W boson, Z bosons, and eight flavors of gluons are counted as separate particles, we have twenty-four particles in total:[6]

Fermions (matter particles):

- Quarks: Up, Down, Charm, Strange, Top, Bottom (six particles);

- Leptons: Electron, Electron neutrino, Muon, Muon neutrino, Tau, Tau neutrino (six particles);

Bosons (four force-carrying particles):

- Photon (electromagnetic force)

- W boson (weak nuclear force)

- Z boson (weak nuclear force)

- Gluons (strong nuclear force):[7]

- r/g: Red-antigreen

- r/b: Red-antiblue

- g/r: Green-antired

- g/b: Green-antiblue

- b/r: Blue-antired

- b/g: Blue-antigreen

- r/α: Red-antialpha (where α represents a color charge different from red, green, or blue)

- α/r: Antired-alpha (where α represents a color charge different from red, green, or blue)

- Higgs Boson

Photon, W and Z bosons, Higgs boson, and eight gluons give us twelve bosons. Together with twelve fermions, we have twenty-four particles.[8]

This is highly significant because the number of ways to arrange a four-letter word is the factorial of four (4!), that is, twenty-four.[9]

The parallel runs much deeper than that. Just as the twenty-four elementary particles of the Standard Model are divided into twelve fermions and twelve bosons, the twenty-four ways to arrange the four letters of the Tetragrammaton are divided into two groups: twelve and twelve. This is because two letters in the name are the same letter heh (H).[10]

Twenty-Six Particles

Yet another way to count elementary particles in the Standard Model is to count antiparticles:

Fermions (matter particles):

- Quarks: Up, Down, Charm, Strange, Top, Bottom (six particles);

- Leptons: Electron, Electron neutrino, Muon, Muon neutrino, Tau, Tau neutrino (six particles);

Gauge Bosons (four force-carrying particles):

- Photon (electromagnetic force)

- W boson (weak nuclear force)

- Z bosons (weak nuclear force)

- Gluons (strong nuclear force)

Scalar Boson

- Higgs Boson (associated with the Higgs field, responsible for the mass of other particles)

So far, we have twelve fermions and five bosons—seventeen particles of matter. Recall that each charged particle has an antiparticle with an opposite electric charge. Since only quarks, electrons, muons, and tau have electric charge, we have nine antiparticles[11]:

Antiparticles:

- Up quark has an anti-up quark;

- Down quark has an anti-down quark;

- Charm quark has an anti-charm quark;

- Strange quark has an anti-strange quark;

- Top quark has an anti-top quark;

- Bottom quark has an anti-bottom quark;

- Electron has a positron as its antiparticle;

- Muon has an anti-muon; and

- Tau has an anti-tau.

Thus, seventeen particles of matter plus nine antiparticles (antimatter) comprise twenty-six particles.[12] This number, of course, is immediately recognizable as the numerical value (gematria) of the Shem Havayah (Tetragrammaton).[13]

Twenty-Six Fundamental Constants

The Standard Model has 26 fundamental constants (or free parameters). These constants are parameters not predicted by the theory but are measured from experiments and observations. The values of these constants need to be input into the Standard Model to make accurate predictions. These constants include:

- Masses of the six quarks (up, down, charm, strange, top, bottom);

- Masses of the six leptons (electron, muon, tau, electron neutrino, muon neutrino, tau neutrino);

- Four parameters that determine the behavior of the weak nuclear force (two for the W and Z bosons, and two others in the CKM (Cabibbo-Kobayashi-Maskawa) matrix, which explains the mixing of quark flavors in weak decays);

- Three parameters for the strong nuclear force (one for the force itself and two for the charge-parity symmetry (CP) violation in Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), the theory of strong interactions);

- One parameter for the Higgs field (the vacuum expectation value related to the masses of the W and Z bosons and the fermions); and

- Eight parameters associated with the potential of the Higgs field, including the mass of the Higgs boson.[14]

This brings the count to twenty-six constants—the numerical value of the Tetragrammaton. The values of these parameters are finely tuned to allow our universe to develop galaxies and planets and, ultimately, intelligent life—the so-called fine-tunning problem.

No matter how we count the elementary particles or the experimentally determined parameters of the Standard Model, they inevitably lead to the proper name of G‑d, Y-H-W-H, which can be seen as the blueprint of the Standard Model.

Endnotes:

[1] Alexander Poltorak, “The Standard Model,” QuantumTorah.com, 05/25/2023, available online at https://quantumtorah.com/the-standard-model/.

[2] Zohar, Rabbi Ḥayyim Vital, Eẓ Ḥayyim, Sha’ar HaKlalim, Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Sefer HaGilgulim, ch. 3.

[3] In some representations of the Standard Model, where W and Z bosons are considered two flavors of the same particle—a quantum of the weak nuclear force—all particles fit into four-by-four grid with the Higgs boson occupying the last cell of the grid. In other representations, where W and Z particles are treated as distinct particles, the Higgs boson (displaced by the Z boson from the four-by-four grid) is added as the seventeenth particle.

[4] See Table 4 in the first installment of the “The Standard Model.”

[5] “The Discovery of the Higgs Boson” by the ATLAS and CMS Collaborations, Phys. Lett., B 716, 1–29, 2012; “Review of Particle Physics” by the Particle Data Group, Phys. Rev. D 98, 030001, 2018.

[6] See, for example, David Griffiths, “Introduction to Elementary Particles,” Wiley-VCH; 2nd edition, October 13, 2008; Wiley-VCH.

[7] Gluons are the force-carrying particles associated with the strong nuclear force. They are responsible for binding quarks together inside protons, neutrons, and other hadrons. Gluons can be associated with different color charges. In the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), which describes the strong interaction, there are eight types of gluons corresponding to different combinations of color charges. These are commonly referred to as “color octets.” While they don’t have individual names, they can be denoted by their color charge combinations.

[8] The number 24 is very significant in Judaism. The Jewish Bible, Tanach, consists of twenty-four books. Priestly service in the Temple was divided into twenty-four watches (mishmarot). In Kabbalah, when written by hand in the Hebrew script Ashurit, the four letters of Tetragrammaton have twenty-four strokes—the so-called “eyes.” The concept of these “eyes” within the letters relates to the belief that each letter contains hidden divine sparks or spiritual energies. These eyes are seen as channels or gateways to higher realms, allowing practitioners of Kabbalah to tap into mystical insights and connect with spiritual forces. Shem Havayah (Tetragrammaton) has twenty-four eyes. Here, the twenty-four “sparks” or “energies” of the Tetragrammaton parallel to twenty-four elementary particles of the Standard Model.

[9] Factorial of a number denoted by the exclamation point, n!, is the product of the number and preceding numbers: n! = n x (n-1) x … x 1. The number of ways to write a four-letter word is the factorial of 4: 4! = 4x3x2x1=24.

[10] In counting 24 ways of writing the four-letter word, we assumed that all four letters were different. Although in the Tetragrammaton, the letter heh (H) appears twice, each letter represents a different sefirah. The first heh represents Binah, whereas the second heh represents Malḵut. This differentiation makes it possible to count them as different letters.

[11] Strictly speaking, according to the Standard Model, every elementary particle has an antiparticle. However, neutrinos and bosons, which do not have an electric charge, are their own anti-particles and, therefore, are not counted.

[12] See, for example, Alessandro Bettini, “Introduction to Elementary Particle Physics,” Cambridge University Press; 2nd edition, April 7, 2014; Francis Halzen and Alan D. Martin, “Quarks and Leptons: An Introductory Course in Modern Particle Physics,” Wiley; First Edition, January 16, 1991.

[13] Tetragrammaton is Y-H-W-H. Yud (Y) is the tenth letter of the alef bet and has a numerical value of ten. Heh (H) is the fifth letter of the alef bet and has a numerical value of five. Waw (W) is the sixth letter of the alef bet and has a numerical value of six. 10+5+6+5=26.

[14] See “Particle Data Group: Review of Particle Physics.”