…And behold, the thorn bush was burning with fire, but the thorn bush was not being consumed.” (Ex. 3:2)

Every theologian worth his salt along with many philosophers, from Plato and Aristotle to Descartes and Kant, attempted to prove the existence of G‑d. Tomas Aquinas, for instance, offered not just one but five “proofs”! Others, such as Hume and Nietzsche, tried proving the opposite. Little did they understand that proving the existence (or nonexistence) of G‑d is a fool’s errand. Here are at least ten reasons why G‑d’s existence cannot be proven (or disproven):

- The existence of G‑d cannot be proven because… G‑d doesn’t “exist,” not in the ordinary sense of existence anyway. One can say that something exists only so long as it may exist or may not. By stating that something exists, we specify one of these two possibilities. Similarly, a person can be alive or, G‑d forbid, not alive. By stating that a person is alive we specify that he is not dead. Such existence is a contingent existence. In this sense, to say that G‑d exists is meaningless, because G‑d cannot not exist! Nonexistence is not an option. Thus, the Maimonides (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, a.k.a. Rambam) writes that G‑d’s existence is “necessary.” Therefore a statement such as “G‑d exists” contains no information, it is a logical tautology.

- Furthermore, G‑d is an absolute and infinite Being and nothing can limit Him. His “existence” is also absolute and is not limited by non-existence. Therefore, to speak of G‑d’s existence is just as meaningless as to speak of His non-existence. This is a manifestation of the principle nimno hanimnaot (not limited by any limitations).

- G‑d is a self-referential construct. In the words of Maimonides, He knows all by knowing Himself. Self-referential statements cause many problems in logic. Think of the Liar’s Paradox: Epimenides said, “All Cretans are liars and I am a Cretan.” If this statement is true, it is false; and, if it is false, it is true. Or take Bertrand Russell’s paradox: if you consider a set of all sets that do not contain themselves, does this set contain itself? If it does, then it doesn’t; and, if it doesn’t, then it does. Or, simply, consider the statement, “This statement is false.” If it’s true, it is false; and, if it’s false, it is true. It is really impossible to make any logical statement about G‑d, because He is a self-referential construct.

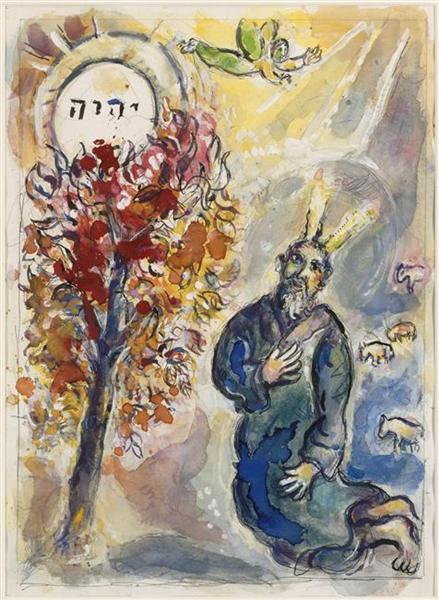

- G‑d is also a self-contradictory construct. Infinite G‑d possesses the power of bli gvul (infinitude) and gvul (finitude); hence, the paradox: Can G‑d create a stone that He cannot lift? This inherent contradiction is symbolized by the burning bush: “…and behold, the thorn bush was burning with fire, but the thorn bush was not being consumed.” (Ex. 3:2)

- A self-contradictory construct does not lend itself to formalization as an axiomatic theory, because in such a theory for every statement A, one can also prove not A. Therefore, every statement is both true and not true.

- As Gödel proved, one cannot prove the consistency of a formal theory by means of this theory. Trying to prove G‑d’s existence in the context of any formal theory would violate Gödel theorem because there is nothing outside of G‑d—ain od milvado.

- Proving the truth of any statement in logic requires precisely defined terms. Furthermore, defining an object entails limiting this object from a larger set of objects. For example, if you want to define a “triangle,” you define it to be a subset of two-dimensional geometrical objects that have certain properties—namely, three lines connected to each other. Or if you wanted to define “circle,” you would define it as a subset of points on a plane equidistant from a given point (called the center of the circle). The definition is always a limitation. We cannot limit infinite G‑d (Ein Sof) in any way. Therefore, we cannot define Him.

- G‑d is above logic. Logic operates on the level of intellect. In the sephirotic scheme, logic exists on the level of Chochma. However, the sephirah of Chochma is not the first. It is preceded by Keter, which in turn is preceded by Adam Kadmon (“Primordial Man”), not to mention that all of these levels are found in the universe of Tikun, which is preceded by the universe of Tohu all of which are all after the Tzimzum (the primordial contraction). G‑d utterly transcends all these levels and our logic and it is silly to attempt to logically define Him, let alone prove His existence.

- We (creations) don’t define G‑d (the Creator); rather, G‑d defines (creates) us. Put another way, transcendent G‑d transcends all definitions. This is why classical theism holds that G‑d cannot be defined.

- For a human being to try to define G‑d is a subtle form of idolatry, as Izhbitzer Rebbe explained in his commentary on the Ten Commandments (see The Theological Uncertainty Principle, and Thou Shall Not Collapse G‑d’s Wavefunction.)

In an axiomatic theory, we start with undefined terms and the relationships between them. For instance, in Euclidian geometry, the undefined terms are point, line, and plane. Then, axioms are formulated and theorems are proved with respect to these undefined terms, as well as further terms defined through them. Thus the only hope we have to make any statement about G‑d is to say that G‑d is an undefined term. This is, essentially, what Kabbalists said long ago by describing G‑d as Ein Sof.

This is exactly what G‑d tells Moses when Moses asks G‑d His name:

And Moses said to G‑d, “Behold I come to the children of Israel, and I say to them, ‘The G‑d of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they say to me, ‘What is His name?’ what shall I say to them?” (Ex. 3:13)

In other words, Moshe is asking G‑d for His name—i.e., for His definition, as it were. G‑d’s answer is truly baffling:

I am who I am” (Ex. I3:14)

This tautological statement, “I am who I am” (alternatively translated as “I will be what I will be”), contains a powerful message: Don’t try to define Me for I am undefinable, ineffable G‑d. It is as if G‑d was saying, “I am who I am, and it is not for you to know who I am.”

…and He said, “So shall you say to the children of Israel, ‘Eh-yeh (I am) has sent me to you.'” (Ex. 3:14)

G‑d tells Moses to explain to his Jewish brethren that the only thing they can know about G‑d is that He is, i.e., that his existence is necessary and absolute, as explained by Maimonides.

However, the very next verse seems to contradict this, as G‑d introduces Himself by His proper name, Havayah (Y‑H‑W‑H):

And G‑d said further to Moses, “So shall you say to the children of Israel, ‘Havayah (Y‑H‑W‑H), G‑d of your forefathers, the G‑d of Abraham, the G‑d of Isaac, and the G‑d of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is My name forever, and this is how I should be mentioned in every generation. (Ex. 3:15)

Didn’t G‑d just reveal His proper name as Havayah (Y‑H‑W‑H)? However, this is not a contradiction. The Tetragrammaton (Y‑H‑W‑H), usually translated as “Lord,” actually means Eternal. Our sages teach that Y‑H‑W‑H is an amalgam of hayah (is), hoveh (was) and yihyeh (will be), i.e. the Eternal. This is a variation on the earlier theme, in which G‑d introduces Himself simply as “I am.” Unlike G‑d, who is the creator of time and exists outside of time, we exist in the temporal dimension. To us past, present and future define the flow of time— indeed, our very existence. If for timeless G‑d it is enough to say, “I am,” for us, temporal creatures, this ontological construct has to be unpacked and spelled out as “I was, I am, and I will be.” Therefore, there is no contradiction between the verses. In this verse, G‑d further elaborates for us that His existence is eternal, unlimited in time or by “non-existence”— i.e., His existence is necessary and absolute and therefore, belies any definition.

We are epistemologically limited in our ability to know G‑d. That is why G‑d stopped Moses when he came towards the burning bush to “investigate this wondrous phenomenon,” saying: “Do not draw near here.” We are limited in our knowledge of the Creator by what He chooses to reveal to us about Himself, as He did to Moshe from the burning bush. That is why it is equally impossible to logically prove or disprove the existence of G‑d. Belief in G‑d always requires a quantum leap of faith.

The problem a person confronts following a once-in-a-lifetime experience of God is that we communicate via human speech, and there is very little vocabulary for reality in an unfamiliar dimension. One can borrow terms from physics such as “non-locality,” but then you have to be prepared to explain quantum theories, which I am not. My instinct is not to try. I’m impressed, however, by the description Aztec philosopher-king Nezhualcoyotl gave an entity he encountered: “The Unknown, Unknowable Lord of All,” for whom he built an empty temple in which no human sacrifices were allowed. Yes, I thought — that guy!