And now thy two sons, who were born unto thee in the land of Egypt before I came unto thee into Egypt, are mine; Ephraim and Manasseh, even as Reuben and Simeon, shall be mine. And thy sons, that thou begettest after them, shall be thine; they shall be called after the name of their brethren in their inheritance. And as for me, when I came from Paddan, Rachel died unto me in the land of Canaan in the way, when there was still some way to come unto Ephrath; and I buried her there in the way to Ephrath—the same is Beth-lehem.” And Israel beheld Joseph’s sons, and said: “Wherefrom are these?” (Genesis 48:5-8)

When Joseph brings Ephraim and Manasseh to Jacob for a blessing, the scene takes a surprising turn. Jacob does not merely bless them; he adopts them:

Jacob tells Joseph, in effect: Your two sons will be mine, like Reuben and Simeon.

That is unprecedented in the Torah’s narrative. And it comes bundled with another puzzle: Jacob then looks at the boys and asks, “Mi eleh?”—“Who are these?”

But Jacob has lived in Egypt for seventeen years. He has watched these grandchildren grow up. How could he possibly be asking who they are?

There are at least three questions we have to hold at once:

- What can Jacob mean by “Mi eleh?” if he plainly recognizes the boys?

- Why does Jacob “take” Ephraim and Manasseh as his own sons?

- Why, in the middle of this adoption, does Jacob suddenly recall Rachel’s death and burial on the road?

1. Adoption as Metaphysics, not Bureaucracy

A simple reading might say: Jacob is arranging inheritance. By adopting Joseph’s two sons, he is giving Joseph a double portion.

That makes legal sense. But the text reads more like something deeper than estate planning. Jacob is not merely distributing property; he is reconfiguring tribal reality. Joseph becomes two tribes. (And the blessing Jacob gives them—placing Ephraim before Manasseh—becomes one of the great “unexpected reversals” of Genesis.)

So what is Jacob really doing?

According to a Chassidic tradition passed down by one of the Baal Shem Tov’s disciples, Rabbi Yisroel Ḥarif of Satanov, in his book Tiferes Yisroel, Jacob was destined to have fourteen sons.[1] At that time, he already had twelve sons, and two more sons were destined to be born to Jacob. Two souls were hovering, as it were, over Jacob’s bed, ready to be born into this world. However, Reuben, Jacob’s firstborn, stood up for the honor of his mother, Leah, and moved Jacob’s bed into Leah’s tent. By doing so, he interfered with destiny. As I discussed in my essay, “Korach Disentangled,” these two souls were later born to Jacob’s son, Joseph, as Ephraim and Manasseh. This is why Jacob rightfully claims these two boys as his own, as they had been destined to be born to him. On this reading, Jacob’s adoption is not symbolic. It is a corrective act—a restoration of a missing completion in the structure of Israel. What appears to be an adoption, at a deeper level, is a reclamation.

This gives us a conceptual bridge to puzzle #2. If the story is secretly about what happens after Rachel’s death—the shift in Jacob’s household, the move to Bilhah, and the consequences of Reuben’s intervention—then Rachel’s burial is not a detour. It is the hinge.

2. Why Rachel Enters the Story?

On one level, Jacob is addressing a painful asymmetry: he is asking Joseph to carry him from Egypt to be buried in the ancestral cave, Me’arat HaMachpelah in Hebron (Ḥevron)—yet Rachel herself was not brought there. Jacob acknowledges the wound before Joseph can voice it.

This also explains why Rachel’s death was relevant to the story and, therefore, answers the first question. To explain to Joseph his motivation for this highly unusual pronouncement, Jacob recalls the passing of his wife, Rachel. This is relevant because, after Rachel’s passing, Jacob moved in with his other wife, Bilhah.

Rachel’s death is not merely backstory; it marks a transition in Jacob’s family architecture. Her passing reshapes the household and sets up the conditions in which Ephraim and Manasseh can become Jacob’s “missing” sons. The Torah is not changing the subject. It reveals the hidden premise. In other words, Rachel’s passing is the context for the fracture that this adoption is now repairing.

3. Why does Jacob ask, “Who are these?”

Now to the strangest question: Mi eleh?—“Who are these?” Jacob has lived with Joseph in Egypt for seventeen years. He surely knows these boys. More than that, it is reasonable to assume that Joseph would want his children steeped in Jacob’s teaching. Indeed, Rashi, commenting on Genesis 48:1, quotes a midrash that states so explicitly.[2] Why would Jacob ask about his grandsons, “Who are these?”

A classical reading understands Jacob’s question not as a failure of recognition, but as a sudden spiritual hesitation. Jacob prepares to bless, but something impedes the flow. Rashi, in a sharp midrashic reading, reframes Jacob’s words: Jacob is not asking for identification; he is asking, “From where did these come—how are they worthy of blessing?”

Now look closely at the Hebrew phrase:

“?מִי-אֵלֶּה” – mi eleh, lit., “who/whence are these?”

The word eleh (אלה) contains the same letters as “Leah” (לאה), only rearranged. That invites a homiletical rereading. Instead of hearing Jacob say, “Who are these boys?”, we can hear a different astonishment:

Mi—eleh?

From Leah—these?!

In other words, Jacob expected to see the spiritual “signature” of Rachel in Joseph’s sons, yet he senses something Leah-like in their root.

So how could Joseph’s sons be “from Leah” in any meaningful sense?

Three paths to Leah

1) Joseph as Leah’s “intended” son

One possibility is that Joseph was supposed to be born to Leah (and Dinah to Rachel), if not for Leah’s prayer leading to the switching of the embryos in utero. After Leah had already borne six sons and was pregnant with her seventh, she prayed that, if the child were male, it would be given to Rachel instead, thereby ensuring that Rachel would have two sons. In response to Leah’s prayer, G-d converted her male fetus into a female, and she gave birth to Dinah (Berakhot 60a). In that framework, Joseph can be physically Rachel’s son while still retaining a spiritual connection to Leah as his “intended” source. That Leah-root could then pass to Ephraim and Manasseh.

2) Reuben’s Attempt to Facilitate Destiny

There is another possible explanation. Twelve sons of Jacob were prophets in their own right. I now tend to think that Reuben might have moved his father’s bed into the tent of Leah, not only because he wanted to protect his mother’s honor. But, as a prophet, he too saw these two souls hovering, ready to be incarnated into two sons to be conceived by Jacob. He further saw that they were destined to be born to Jacob and Leah, but not to Jacob and Bilhah, which is why he moved Jacob’s bed into the tent of Leah. Instead of interfering with destiny, all Reuben wanted to do was help facilitate this destiny!

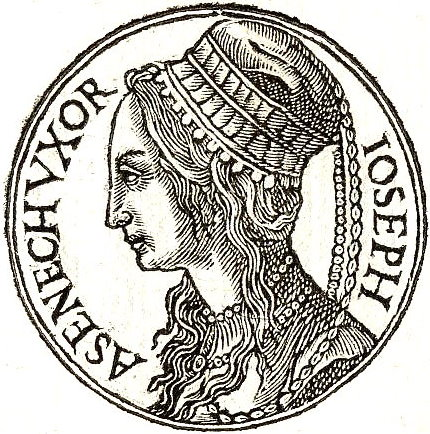

3) Asenath as Leah’s descendant

A third, very different tradition is that Joseph’s wife, Asenath, was not ethnically Egyptian at all. Rather, she was born from Dinah (Leah’s daughter) and sent away, ultimately arriving in Egypt under providential protection, where she would become Joseph’s wife. This possibility[3] comes from the Midrash, which says:

…and he [Shechem] seized her [Dinah], and he slept with her, and she conceived and bare Asenath… He [Jacob] wrote the Holy Name upon a golden plate, and suspended it about her neck and sent her away. She went her way. Everything is revealed before the Holy One, blessed be He, and Michael the angel descended and took her, and brought her down to Egypt to the house of Potipherah; because Asenath was destined to become the wife of Joseph. Now the wife of Potipherah was barren, and (Asenath) grew up with her as a daughter. When Joseph came down to Egypt he married her. (Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 38)

A very similar story is recorded in Midrash Aggadah (Gen 41-45).

If that tradition is accepted, Ephraim and Manasseh are, genealogically, Leah’s descendants: Leah begets Dinah, Dinah begets Asenath, who begets Ephraim and Manasseh.

Either way—through Joseph’s “intended” root, or through Asenath’s lineage—the same answer emerges: there is a meaningful sense in which these boys are “from Leah.”

And it is precisely that which Jacob detects.

4. “God gave me bazeh”: what did Joseph show Jacob?

Now, all pieces of the puzzle fit together. Yes, Ephraim and Manasseh were grandsons of Leah, which is why Jacob exclaimed in amazement, “Are these from Leah?” Joseph replies, “They are my sons, whom G‑d hath given me with this.” The last words in the verse, “with this,” compel Rashi to suggest that Joseph showed Jacob his marriage contract, Ketubah, with Asenath. This explanation begs a question: Even if Joseph had a ketuba, why would Joseph wait seventeen years to show his father a document proving his legitimate marriage?

I suggest a different interpretation: read “With this” (bazeh) not as “here is a document,” but as “here is the sign.” “With this” in Hebrew is “בָּזֶה” (BaZeH). Having the same letters baze is cognate with the word for gold, “זהב” (ZaHaV). What Joseph may have shown his father was the golden plate that Jacob had placed many years earlier around Asenath’s neck. When Jacob recognized the plate and realized that Joseph had married a Jewish girl from his family, the daughter of Leah, his granddaughter, he was pleased and proceeded to bless the lads.[4]

In that moment, Jacob is not merely blessing two children. He is closing a circuit: what was destined but deferred is finally integrated back into Israel.

Incidentally, this novel explanation may also shed light on why Jacob elevated the younger son over the firstborn by deliberately crisscrossing his hands. Dinah, violated by Shechem, conceived by him. Though Dinah herself was guiltless, a child conceived through that unholy act could be understood (in kabbalistic terms) as carrying a mixed spiritual inheritance—kedushah from her mother’s side (Leah) and kelipah (evil) from Shechem. According to a Kabbalistic tradition, Manasseh inherited some of the kelipah from his mother, Asenath, who received it from Shechem, and Ephraim inherited mostly from the holy side of his mother, which is traced back to Leah. Once Jacob realized that Ephraim and Manasseh were born of Asenath, he could have perceived that imbalance. This imbalance is further supported by Rashi’s statement that Ephraim spent his time with Jacob learning Torah from his grandfather, and he was the one who informed his father, Joseph, of Jacob’s illness. On this reading, Jacob’s “switch” was a discerning preference: he placed Ephraim above Manasseh while still blessing them both.

Endnotes:

[1] Rabbi Yisroel Ḥarif of Satanov, Tiferes Yisroel, Warsaw, 1871 (https://hebrewbooks.org/20871). I am grateful to my mentor and friend, Rabbi Bentzion Feldman, for sharing this commentary with me.

[2] Midrash Tanchuma 1:12:6 states that Ephraim was regularly with Jacob for Torah study. He went to Joseph to inform him that Jacob was ill.

[3] These two proposed answers are not mutually exclusive and may complement one another. Joseph and Asenath may have been soulmates in the sense that, whereas Asenath was Leah’s granddaughter, Joseph was Leah’s intended son, who (through Leah’s prayers) was born to Rachel but retained a spiritual connection with Leah’s soul. According to the Arizal, Joseph had a connection to both Leah and Rachel, as his spiritual archetype, Yesod of Zeer Anpin, had a connection to Yesod of Partzuf Leah and Yesod of Partzuf Rachel (see Shaar HaPesukim, parashat Lech Lecha).

[4] This novel explanation does not bear the authority of our sages and, therefore, must be taken with a grain of salt.

Your 1st suggestion regarding why the two Yosef’s sons belonged to Yakov is very logical and the proof is as clear as a chess problem. Rashi’s explanation that Yakov sent away his granddaughter is hard to accept since Jews love their children and grandchildren dearly.

This is not my idea that Yaakov sent his granddaughter away. Midrash Pirkei de Rabbi Eliezer explains that after Dina violated by Shechem became pregnant and gave birth to Osnat, the family was very embarrassed by this offspring of rape. To spare the child this humiliation, Yaakov gave Osnat a golden plate with the holy name of G‑d, as a necklace, placed her under a thorn bush and summoned Archangel Michail to take the baby to Egypt where she was adopted by Potiphar.

Today, I found that Me’am Loez also states that Joseph showed his father the gold amulet that Jacob had placed around Assenath’s neck. Baruch shecheevanti!