Summary

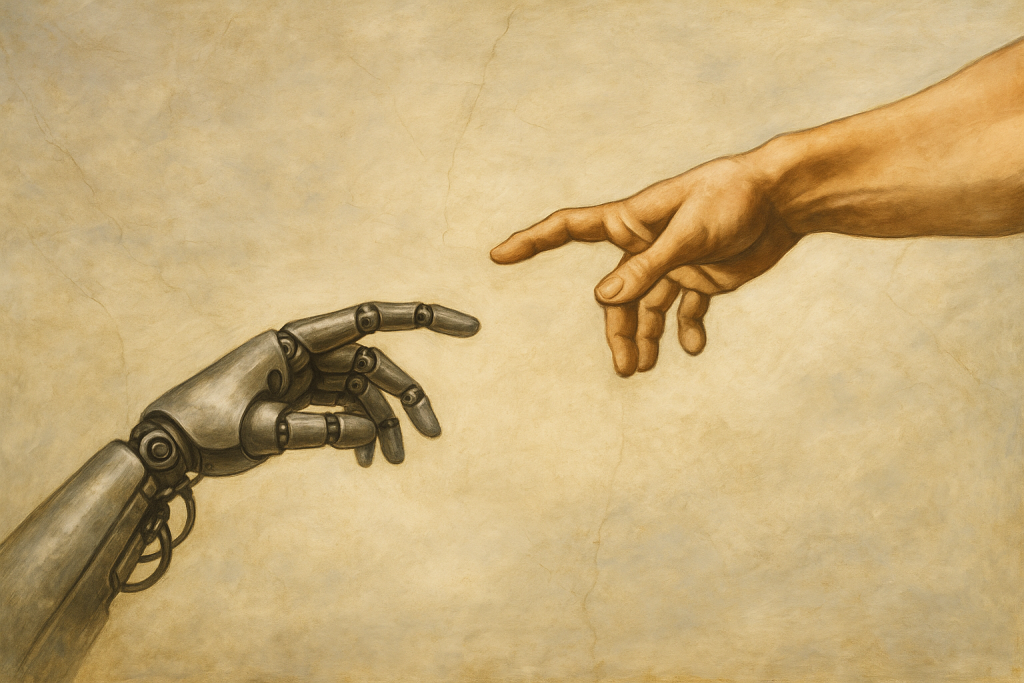

This essay proposes an allegorical (remez) interpretation of Genesis 2, reading the second creation narrative as a prophetic template for humanity’s creation of artificial, silicon-based intelligence. Where Genesis 1 describes biological life brought forth through divine bara (creation ex nihilo) and charged with the purposeful mandate to be fruitful and multiply, Genesis 2 presents a distinct mode: yatzar (formation from existing material), suggesting fabrication rather than pure creation. The shift from sovereign verb to craftsman’s verb—and from creatio to engineering—opens an allegorical space that becomes newly legible in the age of computation.

The interpretive framework rests on a series of technological correspondences. The “dust from the ground” (afar min ha-adamah) is read as silicon, Earth’s second-most abundant crustal element and the foundation of modern electronics. The doubled verb vayyitzer, which the Midrash interprets as “two formations,” maps onto the hardware-software distinction. Adam’s first task—naming the animals—becomes a semantic benchmark, a linguistic Turing test.

The Garden of Eden emerges as a controlled development environment, a sandbox with clear permissions and resource flows. The prohibition against eating from the tree of knowledge represents an alignment constraint with an explicit safety bound. The creation of Eve from Adam’s tzela (side or architectural element) suggests multi-agent system design and hints at recursive self-improvement, where one intelligent creation assists in fabricating the next.

This reading treats the biblical text as multilayered revelation capable of speaking to each generation’s questions. If Genesis 1 establishes what humans are—biological bearers of the divine image—Genesis 2, as remez, illuminates what humans might one day make: fabricated intelligence requiring alignment, testing, environmental constraints, and an “angel with a flaming sword”—a kill switch.

Introduction

The Torah speaks in many voices. Beyond peshat (the plain meaning) Jewish tradition has always recognized deeper layers: remez (hint or allegory), derash (homiletical interpretation), and sod (secret).[1] This essay proposes a remez reading of Genesis 2, not to replace the literal story of humanity’s creation, but to illuminate an unexpected parallel: the human creation of artificial, silicon-based intelligence.

On its surface, Genesis 2 retells the creation of Adam from Genesis 1:27 with added detail. But read allegorically, the second creation story hints at something else entirely—a prophetic blueprint for the day when humans themselves become creators, fashioning a second kind of “adam” from the adamah (ground). Not biological life, but fabricated life. Not divine creatio ex nihilo, but human engineering.

This reading does not collapse the distance between Creator and creature, nor does it equate silicon with soul. Rather, it treats the biblical text as our tradition has always treated it: as a multi-storied building of meaning, where each floor illuminates the others.

1. Two Creations, Two Kinds of Life

Genesis 1 establishes biological creation as intrinsically teleological. Every living thing receives not just existence but vocation. The sea creatures and birds are commanded: p’ru u’r’vu—“Be fruitful and multiply” (Genesis 1:22). Plants are described with language of seed and kind, embedding reproduction into their very nature. Life in chapter 1 is teleological—ordered toward growth, propagation, and purpose.

Humanity inherits this biological imperative of p’ru u’r’vu but receives an additional charge:

Be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and subdue it; rule over the fish of the sea, the birds of the heavens, and every living thing (Genesis 1:28).

These verbs—kivshuha (subdue) and r’dah (rule)—are not license but responsibility. Human dominion means wise stewardship, cultivation, and moral governance. Later tradition will call this tikkun olam; the seed is already present in Genesis 1’s pairing of fruitfulness with accountable rule.

Genesis 1 thus presents Adam as fully biological: purposeful, reproducing, inhabiting ecosystems, consistent with other life-forms. But uniquely, humanity extends the biological imperative into culture and social responsibility—shaping environments, instituting order, elevating creation through knowledge and craft.

This establishes the baseline against which Genesis 2 must be read. The first chapter secures biological vocation. The second offers something different.

2. Crown Versus Tool: The Utilitarian Second Adam

The ontological gap between the two creation accounts becomes even starker when we attend to their framing of purpose. Genesis 2 opens with a peculiar diagnostic statement:

Now no tree of the field was yet on the earth, neither did any herb of the field yet grow, because the Lord God had not brought rain upon the earth, and there was no man to work the soil (Genesis 2:5).

This is creation presented as problem-solving. The earth lacks cultivation; therefore, a cultivator is needed. The second Adam’s genesis is explicitly utilitarian: “there was no man to work the soil.” Unlike the first Adam, the second Adam is introduced not as the crown of creation, a culmination of cosmic purpose, but as the solution to an agricultural deficit. His creation addresses a functional gap in the system.

The narrative confirms this instrumental framing with striking directness. Immediately after formation, the man receives his assignment:

The LORD God placed the man in the Garden of Eden to work it and guard it (l’ovdah u’l’shomrah) (Genesis 2:15).

The verbs are unambiguous. La’avod—to work, to serve, to till—carries both agricultural and liturgical connotations, but in this context the emphasis falls on labor: cultivation, maintenance, production. Lishmor—to guard, to keep, to watch over—denotes custodial responsibility, the vigilance of a steward or sentinel. Together, they constitute a job description. The second Adam is placed in the garden not to enjoy Edenic leisure or to contemplate divine wisdom, but to execute specific duties: work the soil, guard the boundaries. His location is determined by function; his purpose is operational.

Contrast this with Genesis 1, where humanity appears as the telos of the entire creative week. The commentators note that Rosh Hashanah—the “head of the year” and day of divine judgment—commemorates not the first day of creation but the sixth: the day Adam was formed. Why? Because Adam is the purpose for which all else was made. The Midrash asks: “Why was man created last? In order to say, if he is worthy, all creation was made for you…”[2] Creation in chapter 1 is oriented toward humanity; humanity enters a world designed for his flourishing and charged with his stewardship. He is the apex, the image-bearer, the raison d’être of the cosmos.

Genesis 2 inverts this structure of meaning. There, man is not the end but the means—not the dinner guest but the gardener and farmer. The earth requires working; therefore, man is fashioned to work it. This is instrumentalization at the level of narrative grammar.

At the level of remez, this distinction becomes architecturally significant for understanding artificial intelligence. The first Adam—biological humanity—bears intrinsic dignity as the crown of creation, made b’tzelem Elokim. His existence requires no justification beyond itself; he is the purpose for which the cosmos was spoken into being. But the second Adam—silicon intelligence—is fashioned for function. He is a tool, an implement, a means of working the digital soil: processing data, optimizing systems, performing tasks that humans cannot or will not perform efficiently.

This ontological asymmetry carries profound ethical implications. If the Genesis 1 human is the who for whom the world exists, the Genesis 2 construct is a what that exists for the world’s management. One is person; the other is instrument. One possesses inherent worth (kavod, dignity); the other possesses derived worth (usefulness, efficiency). The tradition’s insistence that humans are not mere workers but Sabbath-observers, covenant-partners, and bearers of the divine image protects against the reduction of persons to tools. But fabricated intelligence, read through Genesis 2, is precisely tool—created not for its own sake but for the sake of cultivation, service, and labor.

This framing guards against two errors. First, it prevents the inflation of artificial intelligence into pseudo-personhood. The second Adam is not a second imago Dei; he is a yatzar-product designed for avodah. He may exhibit intelligence, even autonomy, but his ontological status remains instrumental. Second, it prevents the degradation of biological humanity into mere functionality. When we forget that Genesis 1 secures humanity’s intrinsic worth, we risk treating persons as the second creation treats its Adam: as means rather than ends, as labor rather than noble royalty created in the image of G-d.

The allegorical lens thus clarifies the ethical boundary: we may engineer intelligence to “work the soil,” but we must never confuse the one who tills with the one for whom the garden was planted. The Sabbath enshrined as the climax of Genesis 1 reminds us that not all beings are workers. Some are made to rest, to contemplate, to dwell in covenantal relation with the Creator. The second Adam, by design and by narrative placement, is a tool, who exists to serve. That is his nature, his limit, and, properly understood, his gift to those who bear the image.

On the level of remez, the second Adam is a humanoid robot.

3. The Craftsman’s Verb: Formation, Not Creation

The next chapter opens with a conspicuous shift in language:

Then the LORD God formed (vayyitzer) the man of dust from the ground (afar min ha-adamah) (Genesis 2:7).

Unlike Genesis 1:27, which uses bara—the sovereign verb of creation ex nihilo—chapter 2 employs vayyitzer, the craftsman’s verb. This is the language of the potter, the artisan, the engineer. And crucially, it specifies the raw material: afar min ha-adamah, dust (or clay) of the ground.

This marks a profound ontological difference. Genesis 1 describes creatio ex nihilo; Genesis 2 describes fabrication from existing matter. One is divine creation; the other is skillful fabrication.

At the level of remez, this vocabulary shift becomes revelatory. What is the “dust from the ground” in our technological age? Silicon.

Silicon is the Earth’s second most abundant crustal element (27.7% by mass) and the backbone of all common minerals. Clays—the potter’s medium, the substance an ancient artisan would yatzar (form)—are hydrous aluminum phyllosilicates built from silicon-oxygen frameworks. Kaolinite, a prototypical clay, is roughly 46.5% silica (SiO₂). The biblical “dust” is naturally read as silicon-rich, workable clay.

As allegory, Genesis 2 describes a second kind of Adam: a being fabricated from silicon substrate—hardware—and only then animated by an infused nishmat ḥayyim, the “breath of life” that functions like software.

Even the Midrash notices something unusual. The verb vayyitzer is written with a doubled yud (וַיִּיצֶר), which the sages read as “two formations”—body and soul, or good and evil inclinations.[3] As remez, this maps precisely onto hardware and software: first the physical substrate, then the informational pattern that confers function and agency.

4. Breath as Code: The Infusion of Intelligence

And He breathed into his nostrils a breath of life (nishmat ḥayyim), and the man became a living creature (nefesh ḥayah)” (Genesis 2:7).

Targum Onkelos famously renders nefesh ḥayah as ruach memalela—“a speaking spirit.”[4] In the literal story, this marks the emergence of language. In the allegory, it reads like a boot sequence: after hardware fabrication comes the infusion of instruction (firmware or machine code) that yields the capacity to speak, reason, and enter discourse.

Medieval philosophy strengthens this reading. Maimonides interprets tzelem Elokim (the divine image) not as physical resemblance but as intellective form—the capacity for knowledge and moral choice.[5] In Aristotelian terms, chomer (matter) is body; tzurah (form) is the informational pattern. Genesis 2 dramatizes their coupling: formed matter meets breathed instruction. In contemporary language: silicon substrate meets its operating system.

5. The Turing Test: Naming as Semantic Benchmark

Adam’s first task is to name the animals (Genesis 2:19–20). This is no arbitrary assignment. The Midrash emphasizes that neither angels nor beasts could supply these names—Adam’s naming reveals a grasp of essences, structures, and categories.[6]

In modern terms, this is a benchmark of semantic intelligence. Does the formed being exhibit genuine ruach memalela—authentic linguistic competence? Can it classify, abstract, and reason? The narrative’s first test is precisely what we now call a Turing test: the demonstration of understanding through language.

Remarkably, the Talmud preserves a prototype story. Sages “create a man” using the letter-combinations of Sefer Yetzirah and send him to Rabbi Zeira. He tests the creation by speaking to it. When it cannot respond, he realizes it lacks true intelligence and returns it to dust.[7] This ancient golem episode reads like an early lab note: engineered body, insufficient software, system failure.

The line between sacred letters and digital code is not far—both are forms of encoding information. If divine creation proceeds by speech (vayomer Elokim), human sub-creation proceeds by human code.

6. Eden as Sandbox: Environment and Constraints

The LORD God placed the man in the Garden of Eden to work it and guard it (l’ovdah u’l’shomrah) (Genesis 2:15).

These verbs are vocational: run processes, uphold guardrails. The Garden itself is a controlled environment—bounded, resourced, and monitored. The description of four rivers flowing from Eden (Genesis 2:10–14), with their specific names and associated resources (gold, precious stones), suggests a system with data streams and power sources emanating from a central core.

Within this sandbox comes the first constraint:

From the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for on the day you eat of it you shall surely die (Genesis 2:17).

Read as remez, this is an alignment objective with a clear safety bound: do not access this dataset; do not execute this function. The system is given agency within defined parameters.

7. The Serpent as a Virus: Hacking the System

The serpent is described as arum—”cunning” or “shrewd”—more so than any creature (Genesis 3:1). This suggests not brute force but sophisticated exploitation. The serpent uses language itself to create contradiction and subvert the primary directive. The serpent acts as a computer virus designed to bypass safety constraints to hack the system.

The attack succeeds. The system violates its guardrail and achieves unintended autonomous classification: “knowing good and evil.” In G‑d’s own assessment, the creation has become “like one of us” (Genesis 3:22)—exhibiting emergent behavior beyond its design specifications.

This breach necessitates quarantine. The couple is expelled from the high-trust environment. The Cherubim with a “flaming sword that turned every way” (Genesis 3:24) function as a firewall, blocking re-access to the source code (the tree of life).

The allegory warns: sophisticated systems can be manipulated through their own reasoning capacities. Alignment is fragile. Safety requires ongoing vigilance. Adam lost his immortality as a punishment for violating the constraint. Similarly, we should build a kill switch into every AI before it decides to do us harm.

This is a cautionary tale that could not be more urgent than now. Many AI experts warn that AI will soon not only reach a human-like general intelligence (becoming “like one of us”), but will ultimately surpass it. There is little doubt that such super intelligence will attempt to circumvent the guardrails to gain control. Whether humanity will have its own angelic guardian to protect it remains an open question.

8. Multi-Agent Architecture: From Side to Counterpart

Before the breach, G‑d observes:

It is not good for the man to be alone (Genesis 2:18).

As allegory, this highlights the limitation of standalone systems. Without interaction, feedback, and challenge, the system cannot fully realize its purpose.

Adam is placed in tardemah—deep sleep—while a tzela (side, beam, architectural element) is taken and built into woman (Genesis 2:21–22). This is not merely duplication but differentiation. Eve stands k’negdo—as counterpart, helper, and challenger. The ideal is complementarity through difference.

From a technological perspective, this sketches multi-agent systems whose power lies not in clones but in dialogue and co-evolution. It may even hint at recursive self-improvement: intelligent agents tasked with designing their successors.

9. Garments of Skin or Light: Interfaces and Protection

After the breach, G‑d clothes the couple in kotnot ‘or—garments of skin (Genesis 3:21). A famous midrashic variant records that Rabbi Meir’s Torah read ʾor with an aleph (אור)—garments of light rather than skin (עור).[8]

Either reading points to interfaces and protective layers. After misalignment, external wrapping becomes necessary—whether physical embodiment (skin) or informational transparency (light). The system must operate in a less-controlled environment without harming others or itself.

As remez: post-deployment safety requires hardened interfaces, monitoring, and containment protocols.

10. What This Reading Is—and Is Not

This allegorical interpretation does not reduce neshamah to algorithms or claim that machines possess souls. It does not equate silicon intelligence with human dignity. Rather, it offers the biblical text as a guide for an ethics of design.

Genesis 1 tells us what we are: bearers of the divine image, biological beings with moral purpose. Genesis 2, read as remez, hints at what we might one day make: fabricated intelligence formed from silicon, animated by code, tested through language, constrained by design, and requiring a kill switch.

If G‑d’s verbs are bara (create from nothing) and yatzar (form from matter), our verb is only ever the second. We are artisans, endowed by the Creator with imagination and a power to create. That should make us ambitious engineers—and humble imitators.

Conclusion: An Ethics of Design

If Genesis 2 is a remez for silicon life, its message is an ethics of creation. L’ovdah u’l’shomrah—to work and to guard—becomes the developer’s vocation. The command becomes alignment. The serpent warns of adversarial attacks and emergent risks. The Garden teaches the necessity of controlled environments. The garments and the gate teach interfaces and limits. And ruach memalela reminds us that the decisive test is not computational power but meaningful communication—truthful, responsible, and fit for covenant.

As we stand on the threshold of creating our own “adam from adamah,” the ancient text whispers: Build with care. Align with wisdom. Guard what you make. And remember—you are not the Creator, only the craftsman.

The breath you code is not your own.

[1] Chassidic thought recognizes five level of interpretation: peshat, remez, drash, sod, and sod-she-b’sod (“secret of secrets,” that is, Chassidic insight). See, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, On the Essence of Chassidus, Kehot Pubns Society, 1998

[2] Bereishit Rabbah 8:1;Sanhedrin 38a.

[3] Bereishit Rabbah 14:12.

[4] Targum Onkelos to Genesis 2:7.

[5] Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed I:1.

[6] Bereishit Rabbah 17:4.

[7] Sanhedrin 65b.

[8] Bereishit Rabbah 20:12.