And out of the ground made the Lord G‑d to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; and the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. (Genesis 2:9)

And the Lord G‑d commanded the man, saying: “Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it; for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.” (Genesis 2:16–17)

Upon creating Adam and Eve, G‑d permitted them to eat any fruit from the Garden of Eden, except for the forbidden fruit—the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Disregarding this injunction, Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit and forever changed the history of the world. This may be one of the most bizarre stories in the Torah. There are different opinions about what was the forbidden fruit—grapes, a fig, an olive… Most of us regularly eat grapes, figs, and olives. However, we become no smarter from eating these fruits or less moral. It is hard to understand this narrative in a literal sense…

What is the significance of the tree’s being called the Tree of Knowledge? What knowledge did Adam and Eve acquire by eating its fruit? Why was the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge forbidden? Moreover, why was this sin so catastrophic that it merited punishment with death and the loss of Paradise?

Before the commission of this sin, the first humans had freedom of choice—they knew true and false, right and wrong; they knew that eating the forbidden food of the Tree of Knowledge was wrong, because they had been told so by G‑d Himself. In fact, the only thing they knew was true and false. The concepts of good and evil were unknown to Adam and Eve before the Sin of the Tree of Knowledge (Ḥet Eitz HaDa’at). It was precisely this knowledge that they acquired by eating the forbidden fruit. Presumably, the Tree of Knowledge was more fully called the “tree of the knowledge of good and evil” for no other reason than that it was the source of the knowledge of good and evil. Indeed, in attempting to persuade Eve to eat the forbidden fruit, the cunning serpent suggests that as the very reason that G‑d did not want them to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil:

For G‑d doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as G‑d, knowing good and evil.” (Genesis 3:5)

By eating from the Tree of Knowledge, Adam and Eve acquired the knowledge of good and evil. What was so terrible about their acquisition of this knowledge that they deserved capital punishment? What is wrong with knowing good and bad (evil), and how does it differ from knowing true and false or right and wrong?

In his Guide for the Perplexed, Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (a.k.a. RaMBaM or Maimonides) explains that the better Adam (and Eve) understood the concepts of good and evil, the less they were able to differentiate true and false or judge right from wrong:

…the intellect, which was granted to man as the highest endowment, was bestowed on him before his disobedience. With reference to this gift, the Torah states that “man was created in the form and likeness of G‑d.” . . . Through the intellect, man distinguishes between the true and the false. This faculty Adam possessed perfectly and completely. . . . Thus, it is the function of the intellect to discriminate between the true and the false—a distinction which is applicable to all objects of intellectual perception. . . . When Adam was yet in a state of innocence and was guided solely by reflection and reason . . . he was not at all able to follow or to understand the principles of apparent truths [i.e., moral issues of good and bad]; the most manifest impropriety, viz., to appear in a state of nudity, was nothing unbecoming according to his idea: he could not comprehend why it should be so. After man’s disobedience, however, when he began to give way to desires which had their source in his imagination and to the gratification of his bodily appetites, as it is said, “And the wife saw that the tree was good for food and delightful to the eyes” (Gen. 3:6), he was punished by the loss of part of that intellectual faculty which he had previously possessed. . . . Then he fully understood the magnitude of the loss he had sustained, what he had forfeited. . . . Reflecting on his condition, the Psalmist says, “Adam, unable to dwell in dignity, was brought to the level of the dumb beast” (Ps. 49:13). (The Guide for the Perplexed, Part 1, Ch. 2)

This is very perplexing, indeed! Maimonides is telling us that so long as Adam (and Eve, of course) had been granted intellectual faculties, which provided the ability to know true and false and discern right from wrong, Adam and Eve were unable to comprehend the notions of good and evil. To wit, they did not see anything wrong in being naked. However, after the sin, the situation reversed—having gained the ability to see good and evil (and, consequently, becoming ashamed of their nudity), the first humans lost some of their intellectual prowess and the ability to know true and false. How are we to understand this? Why does the knowledge of good and evil preclude—or why is it incompatible with—the knowledge of right and wrong?

The Superposition of States and Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

Let us summarize what Maimonides says: Adam could know either true and false (right and wrong), or good and bad (evil), but not both. The more he learned the latter, the more he lost the ability to know the former. This is structurally similar to the superposition of states and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics. (I am very grateful to my son-in-law, Maimon Kirschenbaum, for pointing this out to me.)

The essence of the uncertainty principle, first formulated by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, is that two complementary variables (In physics, such pairs of variables are called canonically conjugate variables; examples of such pairings include coordinates and momenta, or time and energy.) cannot be known simultaneously with precision—the more precisely we measure one variable, the more uncertain the other variable becomes. For example, the more precisely we know the position of a particle, the less certain we are of its momentum, and vice versa. (The Heisenberg uncertainty principle states: Δx×Δp ≥ ½ћ, where Δx is the uncertainty in the measurement of the position x, Δp is the uncertainty in the measurement of the momentum p, and ћ is the reduced Planck constant h/2π.) In quantum mechanics, it is always a trade-off: the more we know of one characteristic of an object, the less we know of the other complementary characteristic.

In the story of the Tree of Knowledge, we are presented with a pair of complementary characteristics: truth and false (right and wrong) on the one hand, and good and bad (evil) on the other. This is why the tree is called the tree of the knowledge of good and evil—because by tasting its fruit the first humans acquired knowledge of good and evil, but lost their knowledge of right and wrong.

The Superposition of States

I touched on quantum superposition earlier in my essay “Two Beginnings.” Let us now examine more closely the superposition of states in quantum mechanics.

The philosopher of physics David Albert gives the following example, as paraphrased here (see chapter 1 of David Z. Albert, “Quantum Mechanics and Experience,” Harvard University Press, 1992).

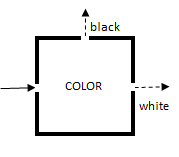

Let us suppose that a subatomic particle (say, an electron) has a property we are going to call “color” (it could be the spin of an electron, or the polarization of a photon, etc.). Whatever we mean by “color,” this is a binary property that has only two values—black and white. We can build a color box that has three apertures: one for letting in all (that is, both types of) electrons, one for letting out black electrons, and one for letting out white electrons. The color box does not change the color of the particles that enter it. If we were to send into it a single white electron, it would always (100% of the time) exit through the white aperture and, likewise, if we were to send in a single black electron, it would always exit through the black aperture. The only thing the color box does is to test the color of the electrons and to sort them accordingly. It is a color-sorting apparatus, nothing more.

If we mix some black electrons with some white electrons and send them all through the inlet aperture on the left of the box as shown in Figure 1, all the black electrons will exit through the black aperture at the top of the box, and all the white electrons will exit through the white aperture on the right.

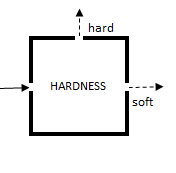

Let us suppose that a particle (say, an electron) also has a property we are going to call “hardness.” Like color, hardness is a binary property that has only two values—in this case, hard and soft. We can also build a hardness box that has three apertures: one for letting electrons in, one for letting out hard electrons, and one for letting out soft electrons.

If we mix some hard electrons and soft electrons together and send them through the inlet aperture on the left, all the hard electrons will exit through the hard aperture on the top of the box, and all the soft electrons will exit through the soft aperture on the right, as shown in Figure 2. We build the hardness box so that it does not change the hardness of the particles that enter it. If we were to send a single soft electron into the inlet aperture, it would always (100% of the time) exit through the soft aperture. Similarly, if we were to send in a single hard electron, it would always exit through the hard aperture. The only thing the hardness box does is to test for hardness and sort the electrons accordingly. It is a hardness sorting apparatus, nothing more.

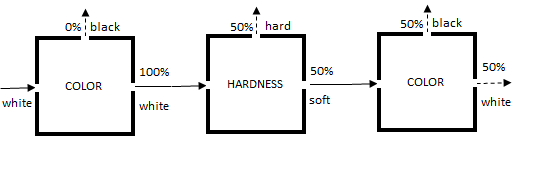

Let us now line up three boxes: a color box, a hardness box, and another color box.

In this experiment, we send only white electrons into the first color box shown on the left of Figure 3. We already know that the color box does not change the color of the particles that pass through it. Therefore, we expect to see 100% of the electrons exiting through the white aperture on the right of the color box. And this is exactly what happens. The white electrons exiting the first color box now enter the hardness box in the middle of Figure 3. The hardness box sorts out the electrons according to their hardness characteristic, with 50% of the electrons exiting through the hard aperture (those are the hard electrons) and 50% exiting through the soft aperture (those are the soft electrons). Now, let us feed all soft electrons exiting from the soft aperture into the second color box on the right of Figure 3. What do we expect to see? We should reasonably expect to see all those electrons exiting the second color box through the white aperture. Indeed, since we sent only white electrons into the middle box, and the middle box supposedly does nothing to these electrons except for checking their hardness, their color should not—or so it seems—be affected. However, surprisingly, this is not what happens. In the second color box, fifty percent of the electrons exit through the white aperture, and 50% of the electrons exit through the black aperture. This means that the second color box encountered 50% white electrons and 50% black electrons. But from where did the black electrons come from?

This paradoxical result has been verified in countless experiments, which invariably produce the same outcome. It turns out that as soon as we discover information about the hardness of the electrons, we erase all knowledge about their color characteristics. Although we started knowing that 100% of the electrons entering the first color box were white, after measuring electron hardness in the hardness box, this information is lost, which means that there is an equal probability of finding at random a white or a black electron at the end of the three-box process. It is not that the electrons are “actually” white, but the hardness box changes the color of some of the electrons. The hardness box does not change the color, but in the process of measuring the hardness of the electrons, the hardness box erases any information of their color, which means we have an equal probability of finding a white color or a black one.

In other words, the electrons, whose hardness characteristic is precisely known to us, have their color characteristic in a state of superposition: their color is neither black nor white nor both nor neither, but is in the state of superposition of black color and white color—the fifth state unknown to classical (Newtonian) physics.

This thought experiment, therefore, illustrates the concept of superposition of states. Whereas in classical physics, a system can be only in one state at any moment in time, in quantum mechanics, the system could be in a superposition of states. For example, if we spin a Chanukah dreidel (top), it will spin either clockwise or counterclockwise, depending on which direction we spun it. In quantum mechanics, a top can be in a superposition of states of spinning clockwise and counterclockwise. In fact, physicists routinely put electrons in the superposition of states of having spin up and spin down, which is roughly equivalent to spinning clockwise and counterclockwise.

This experiment also illustrates the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, according to which, as we have said above, a state where one of the two complementary characteristics has a definite value somehow corresponds with a superposition of many states for the other characteristic thereby making it indefinite.

This is precisely what is going on in the Torah narrative of the Tree of Knowledge! As mentioned above, in quantum physics “color” and “hardness” are just placeholders for any complementary (i.e., “canonically conjugate”) characteristics. In applying this concept to the Torah narrative, let us replace “color” with the absolute objective truth about right and wrong so that black and white colors represent right and wrong, respectively. Similarly, let us replace “hardness” with “goodness” so that hard and soft correspond to good and evil, respectively.

For as long as Adam and Eve were endowed with the intellectual prowess to know right and wrong precisely, the complementary knowledge of good and bad was in the state of superposition—the first humans, before their primordial sin, were ambivalent about good and evil. After the sin, the situation flipped, as in our example with the three boxes above: the knowledge of good and evil that came with the forbidden fruit put the knowledge of right and wrong into the state of superposition. Thus, Adam and Eve could no longer distinguish between true and false, between right and wrong—and with that inability came the loss of Paradise. As we see, the tree of knowledge of good and evil served as the “hardness” box, as it were, in the three-box assembly above, erasing the information about true and false from the minds of Adam and Eve. The Tree of Knowledge thus acted as the quantum eraser. (For mathematically inclined readers and the readers familiar with quantum mechanics at least on the introductory level, I will post, bli neder, the mathematical treatment of these ideas separately.)

The Ego and the Loss of Paradise

To be able to discern between true and false, to know right from wrong, is a matter of judgment. It is an intellectual judgment, which does not require and, indeed, does not permit any emotional involvement. A judge must be independent and have no self-interest in the matter at hand. Thus, one’s ego cannot be involved in the process. The problem is that once an ego gets involved, it tends to insert itself into every aspect of one’s life or thoughts. Having an ego, one can no longer objectively decide between right and wrong, because one’s decision-making is tainted by one’s emotional involvement and self-consciousness, by one’s ego.

The knowledge of good and evil, on the other hand, is just the opposite of the knowledge of true and false—it requires the emotions and ego. Unlike true and false, which are objective and absolute categories, good and bad are always relative to the person making the judgment—is it good for me? The ego sets the point of reference, with respect to which good and bad are decided. The involvement of the ego necessary to know good and bad precludes the objectivity necessary to know right and wrong—hence the mutual incompatibility. The change of the perspective from the abstract true and false to the emotional is it good for me, or is it bad for me is a paradigm shift in human consciousness of cosmic proportions—the end of the age of innocence.

After the primordial sin of Adam and Eve, all humans have an ego, and we all lack the intellectual ability to judge right and wrong objectively. If pre-sin clarity was called Paradise, after the sin, Paradise was lost.

It is interesting to note that in all spiritual traditions, the path to spiritual enlightenment and union with the Divine (unio mystica or, in Hebrew, devekut) lies through the practice of asceticism. People who seek honor, power, or base transient pleasure through sexual or other sensory indulgencies have no hope of achieving spiritual enlightenment, which is seen as incompatible with any form of self-gratification.

Commenting on the verse, “I shall remove sickness from your midst,” the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, says,

The sickness mentioned here . . . refers to the source of all sickness, i.e., the feeling of self-consciousness that was caused by the sin of the Tree of Knowledge. Before the sin, there was no concept of self-consciousness, as reflected in the verse: “and they were both naked, and they were not ashamed.”(Genesis 2:25) The sin led to the feeling of self-consciousness, as reflected in the verse: “and the woman saw that the tree was good to eat.” (Genesis 3:6) … The sin of the Tree of Knowledge had an effect on everyone, even on the righteous. (Lessons in Sefer HaMaamorim, Selected Discourses of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, “Lo Sih’yeh Meshakeila,” pp. 168–173.)

The Rebbe further speaks of four people discussed in the Talmud (tr. Shabbat 55b, tr. Baba Batra 17a.) who died not because of their own sins, but due to “counsel of the serpent.” The primordial snake injected his poison into all of humanity, and even the best of best have a minute dose of that poison—the self-consciousness stemming from one’s ego. Even completely righteous people, who are selflessly dedicated to serving G‑d, still have a drop, however small, of that poison from the primordial snake. It has become part of our spiritual and psychological DNA.

Now, perhaps, we can also understand why the prohibition against eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge carried the threat of such harsh punishment—death. Before that sin, humans were meant to live forever; there was no inflated ego desiring self-gratification and, therefore, no need for death. That evil was imbedded in the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge and was, therefore, external to any human being. Upon tasting the forbidden fruit and internalizing the evil, the first humans inflated their ego and acquired the egotistic desire for self-gratification. This, perhaps, brought about the need for death as a means to rectify the human ego, because death is the ultimate self-nullification.

The messianic redemption, which in many ways harkens back to the pre-sin innocent age of Paradise, is seen as the stage in human history after the primordial sin has been atoned for, and human ego has been rectified to the point that it requires no further nullification, which automatically removes death from the world. The messianic era, therefore, is the stage of Paradise when we return to the state of intellectual enlightenment when we once again shall know right and wrong, but not know good and bad. It seems that the uncertainty principle will hold even in messianic times. May it happen immediately!

Outstanding piece! I was going to say that it seems both good and true, but I want to avoid quantum superpositions…

Thank you for posting this article. Though I am not Jewish, I do have a strong interest in the Old testament, in history, and in Physics. It was very interesting for me to read this treatment of what I personally believe true about mankind. It does seem that the more we learn, the less intelligent we become on the whole, to the point where our overstated sense of self importance inevitably becomes our own undoing. Never in our history have more people had more college degrees than now, and yet instead of helping us become wiser and more reflective of the greater view of things (G‑d’s perspective), here we are now on the verge of destroying the rule of law, and with it democracy and civilization itself. “Pride goes before a fall” was coined by Salomon over 2500 years ago, underscoring the fact that we have known this is one of our greatest weaknesses for a very long time. And yet despite that clear understanding, we still keep pushing civilization into the abyss (e.g. the fall of Jerusalem, the Roman empire, the Ottoman empire, the Spanish empire, etc.). And now here we are again pushing civilization to the brink of collapse. I would not have believed it possible — that we could be this stupid — had I not seen it happening in my lifetime with my own eyes.