Isaac’s Blessing

Stars, Sand… and Silence

Abraham’s blessings sparkle with cosmic imagery—stars above, dust below. But when God blesses Isaac, the patriarch of gevurah, something extraordinary happens: the metaphors vanish. In their place—pure mathematical simplicity.

When G‑d first blesses Abraham, He says his descendants will be “like the dust of the earth” (Genesis 13:16). Later, G‑d expands the image: “like the stars of the heavens” (Genesis 15:5). Two metaphors—dust below and stars above—capturing opposite poles of possibility.

But when G‑d blesses Isaac, the blessing is astonishingly plain: “I will multiply your seed.” (Genesis 26:24)

No stars. No sand. No metaphors. No imagery whatsoever… Just silence. This silence is not absence but presence—the kind of quiet that exists at the eye of a hurricane or at the event horizon where all trajectories converge. In information theory, maximum compression yields minimal expression. Isaac’s blessing is maximally compressed: pure signal, zero noise.

Why does Abraham receive two metaphors, and Isaac receive none?

Abraham: Ḥesed and Outward Expansion

Abraham embodies ḥesed (“kindness”), which is giving, loving, expanding, radiating outward in all directions. In physics language, ḥesed acts as a centrifugal spiritual force, moving away from the center in all dimensions.[1] When you expand outward, you can rise high or fall low.

Thus, two metaphors:

- Stars — rising to transcendent heights

- Sand/dust — sinking to the lowest point

This duality contains both promise and peril. The Midrash captures this polarity: “When Israel rises, they are like the stars; when they fall, they are like the dust.”[2]

Ḥesed, when holy, builds worlds, but unbounded ḥesed can spill into distortion. Unchecked, a kindness can be misdirected. Ḥassidic sources explain that the passion in forbidden relations is not a “separate” evil drive, but ahavah nefulah—love fallen from midat ha-ḥesed. The Torah itself alludes to this by calling incest “ḥesed hu” (Lev. 20:17); the Baʿal Shem Ṭov, and after him R. Naḥum of Chernobyl, read this as ḥesed that has overflowed its proper boundaries of gevurah and descended into sexual immorality.[3] Expansion always includes risk, because it generates many possible outcomes.

To visualize Abraham’s mode, imagine an inflating sphere: Outward motion in all directions requires multiple metaphors—because there are multiple horizons.

Isaac: Gevurah and Inward Convergence

Isaac represents gevurah—strength, restraint, introspection, inward movement.[4] If ḥesed expands, gevurah contracts. In physics language, gevurah acts as a centripetal spiritual force, moving toward the center from all dimensions. Isaac’s life is the embodiment of inwardness: unlike Abraham or Jacob, he does not travel widely. Instead, he digs wells, revealing the waters hidden beneath layers of earth.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe explains that well-digging is a metaphor for revealing the essence already present in the soul.[5] Inward movement has one destination only: the center—the divine core within.

When you move inward, there is no duality, no “stars” vs. “sand.” There is no branching into multiple outcomes. Essence is singular. Thus, Isaac’s blessing needs no metaphor. No imagery. No polarity. Only essence.

Consider the physics of well-digging: you remove matter (earth) to reveal what was always there (water table). This is subtractive revelation. It is somewhat akin to what we call in quantum field theory, “renormalization”—stripping away infinities to reveal finite truth. In the case of Isaac, he was stripping away finite levels of dirt to reveal “living waters,” a metaphor for the infinite godly soul—reḥovot.

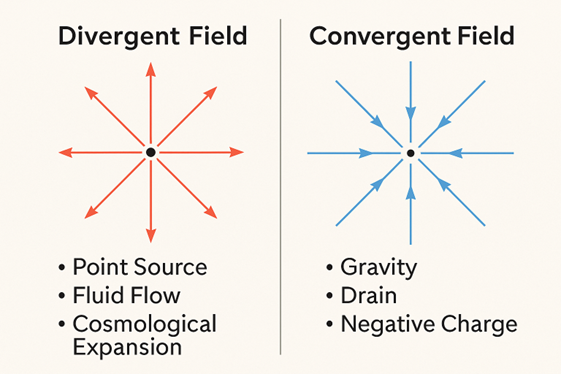

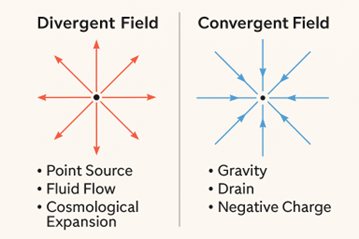

In the language of vector calculus, Abraham’s ḥesed has positive divergence—flow emanating outward from a source. Isaac’s gevurah has negative divergence—flow converging toward a sink. This isn’t mere analogy; it’s structural isomorphism.

Scientific Parallel: Divergent vs. Convergent Fields

Modern physics illustrates this Torah wisdom through field theory by giving us an exact analogue: Abraham is emblematic of a divergent field (outward expansion).

Examples include:

- the radial electric field of a positive charge[6]

- fluid flow from a spring or source[7]

- heat flow from a hot point[8]

- cosmological expansion[9]

These fields radiate omnidirectionally with positive divergence. They admit many possible trajectories—just like ḥesed.

Isaac, on the other hand, is symbolic of a convergent field (inward focus).

Examples include:

- gravity, pulling everything toward a mass[10]

- fluid draining into a sink[11]

- the electric field of a negative charge[12]

- gradient flow toward a single energy minimum[13]

These fields converge toward one center; their divergence is negative. There is only one outcome—just like gevurah’s inner journey.

Abraham’s outward flow requires metaphors (because outward motion contains many modes).

Isaac’s inward flow requires none (because inward motion reaches only one truth).

Mathematically, ∇·F > 0 for divergent fields (Abraham), while ∇·F < 0 for convergent fields (Isaac). The blessing’s structure mirrors the mathematics: multiple terms for positive divergence, singular expression for convergence.

The Quantum Perspective: In quantum mechanics, measurement collapses infinite possibilities into one outcome. Abraham’s mode is pre-measurement—the superposition of all possible states (stars AND dust). Isaac’s mode is post-measurement—the collapsed eigenstate. His blessing needs no metaphor because essence, like a measured quantum state, is singular.

Takeaway

Abraham teaches us how to expand—how to reach out, build, give, and shine. This outward work is noble but carries vulnerability and variation.

Isaac teaches us that sometimes the effort must be directed inward: peeling back layers, digging our own wells, finding the spiritual water already inside us. That path has one direction and one outcome—our own divine center—yehidah—the singular essence of the godly soul.

Some blessings come dressed in metaphor—stars to inspire ascent, dust to ground us in humility. But Isaac’s blessing comes naked, unadorned, essential. It teaches us that the deepest truths need no embellishment. When you reach the center—whether through physics, mysticism, or lived experience—you find the same thing: a silence more eloquent than any metaphor, a unity that renders all comparisons obsolete.

Today’s Quantum: Choose between expansion and convergence. Are you in an Abraham moment—needing to radiate outward, touch many lives, explore possibilities? Or an Isaac moment—needing to dig inward, strip away layers, find your essential point? Both are holy. Both are necessary. But knowing which mode you are in changes everything.

[1] Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, Tanya, Iggeret HaKodesh 12; see also Torah Or, Lech Lecha.

[2] Bereshit Rabbah 44:12.

[3] Baʿal Shem Tov. Baʿal Shem Tov ʿal ha-Torah, Parashat Kedoshim, §27; R. Naḥum of Chernobyl, Meʾor ʿEinayim, Lekh Lekha §2 and Pinḥas §7; Sifra to Lev. 20:17.

[4] Zohar I:137a; cf. R. Chaim Vital, Etz Chayim, Sha’ar HaHakdamot, ch. 1.

[5] Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, Likkutei Sichos, vol. 5, Parashas Toldot, Sichah 1.

[6] A positive electric charge creates an outward radial electric field E:

Divergent at the source (positive charge generates flux outward).

[7] Imagine water emerging from a spring at the origin:

Fluid flows outward in all directions — a classic source field.

[8] Temperature gradients around a hot object produce heat flux outward — another divergent field.

[9] On large scales, galaxies recede from each other due to metric expansion:

Vectors point outward everywhere — expansion in all directions.

[10] The gravitational field vectors point inward:

Matter acts as a sink — a perfect convergent field.

[11] Fluid flow into a drain or sink:

All flow lines move inward. No branching. No alternatives. One destination only.

[12] A negative charge is a sink for electric flux:

[13] In physics and optimization:

Systems move inward toward a single energy minimum—a single “center.”