Synopsis

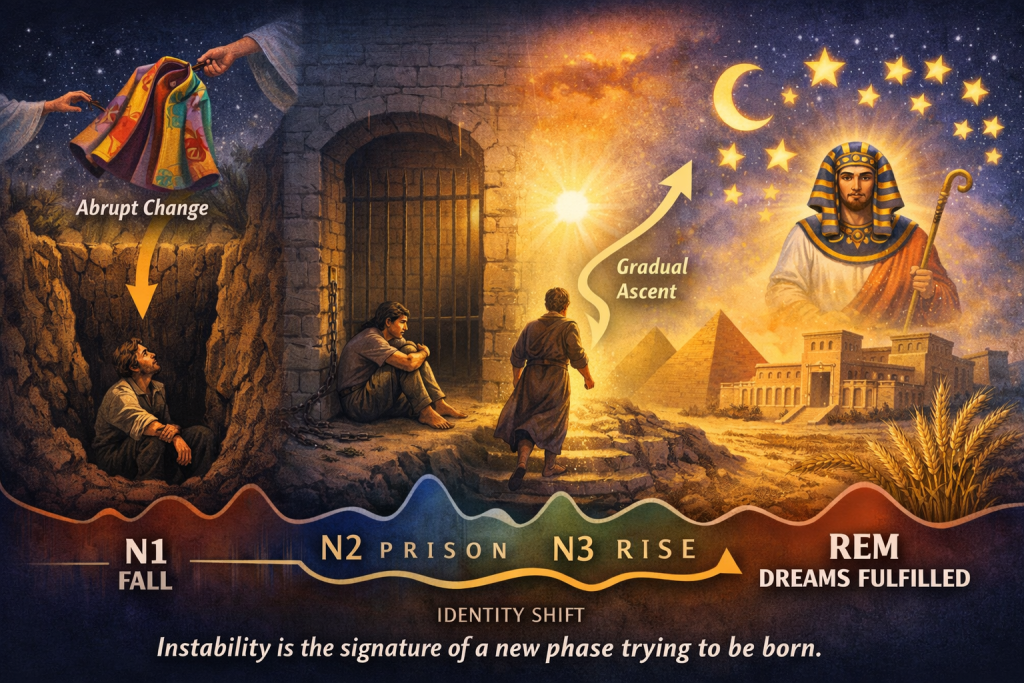

The Joseph narrative in Genesis is stitched together with dreams—his own, the courtiers’, Pharaoh’s—yet the story itself unfolds according to the grammar of sleep. This essay maps Joseph’s life onto the architecture of sleep stages (N1, N2, N3, and REM) and interprets the dramatic transitions between his life epochs through the physics of phase transitions. The recurring motifs of pits and garments emerge as markers of first-order transitions: moments of instability that precipitate abrupt shifts from one energy basin to another. Joseph’s final ascent, by contrast, exhibits the hallmarks of a second-order transition—a gradual reshaping of the landscape until the old state simply dissolves. Read this way, the Joseph story becomes a meditation on the dynamics of personal transformation: the necessary shedding of old identities, the passage through intermediate states of consolidation, and the emergence of deeper coherence from apparent chaos.

The Joseph narrative is enmeshed with dreams: Joseph’s own double dream, the paired dreams of Pharaoh’s imprisoned courtiers, and Pharaoh’s double dream that shakes an empire. What makes the story unique is not only that Joseph dreams, but that he lives as if he were enacting his dreams—a hidden blueprint for unfolding reality.

This is why Joseph’s story reads less like a straight line and more like a recurring dream sequence: scenes repeat, symbols return, and each recurrence is a hinge that flips him into a new state of being.

1. The Recurring Dream Motif: Pits, Garments, and Instability

Joseph’s life falls naturally into three visible epochs: (1) his youth in Jacob’s home, (2) his descent into Egypt as a slave and then as a prisoner, and (3) his ascent to power as Egypt’s viceroy. Between epoch (1) and epoch (2) he is cast into a pit; between epoch (2) and epoch (3) he is cast into another “pit”—a dungeon. Two descents. Is it a coincidence?

Before throwing Joseph into a pit, the brothers argued over whether to kill him or not. Similarly, Potiphar’s wife argues with Joseph, “Lie with me!” Joseph refuses and runs off. Another coincidence?

And then there are the garments. Before the brothers throw him into the pit, they strip him of his ketonet—his colorful tunic, the garment that marked him as the visible sign of a special place in the family. Before Potiphar throws him into prison, Joseph is again stripped—this time when he flees Potiphar’s wife, leaving his cloak in her hands. Two removals of clothing, each immediately preceding a fall into a pit. A third coincidence?

The pattern is too clean to dismiss as a coincidence. It reads like the grammar of sleep and nonlinear dynamics: attractor basins punctuated by instabilities that precede a state change.

A garment is never merely fabric. A garment is a role, an identity, a presentation—the interface between the inner self and the outer world. To strip someone is to unmake their social “self” and expose them to a new, unstable boundary condition. Joseph is not only being removed from a place; he is being removed from a definition.

If you want a single line for what the garment symbolizes in both scenes, it is this: the shedding of an old identity so that a new one can form. In physics terms, it is the collapse of an old “order parameter”—a macroscopic marker of the state the system was in. In human terms, it is the painful grace of becoming undefined.

2. Joseph’s Life as Sleep Architecture

If Joseph’s life is dream‑shaped, it should resemble the architecture of sleep. Modern sleep science distinguishes several stages—N1, N2, N3, and REM—that cycle through the night in a patterned rhythm. REM (Rapid Eye Movement) is strongly associated with vivid, narrative dreaming (although dreams can occur across stages, the dreams we remember are usually those we saw during REM sleep); non-REM stages, especially N3 (slow-wave sleep), are also associated with memory consolidation, stabilization, and deep restoration.

To map Joseph onto sleep is not to force allegory; it is to notice that the story already behaves like sleep: alternating depths, punctuated by abrupt transitions, with memory and meaning reorganized in the dark.

2.1 REM: the adolescent dream of destiny

Joseph’s two prophetic dreams occur in the first epoch, in the “father’s house.” This is the REM‑like phase of his life: vivid narrative, rich symbolism, and a sense of destiny that feels more real than the present. REM dreams often amplify emotion and social meaning; they turn the interpersonal field into theater. In Joseph’s dreams, the family becomes a cosmos—sheaves bow, stars align, and the household turns into an astronomy of souls.

But REM also carries a danger: dreams feel so compelling that we confuse the image with its timing. Joseph is right about what he saw, but naïve about when and how such realities can unfold. A dream disclosed too early can wound the very relationships it foretells.

2.2 N1: the liminal descent—slave in Potiphar’s house

The first stage after wakefulness is the drowsy stage, NREM 1 (N1). It is the threshold state: orientation wavers, the self loosens, and the mind is not yet reorganized. Joseph’s slavery is an N1‑like existence. He is no longer who he was, but not yet who he will be. He is between languages, between names, between worlds, learning the new “physics” of Egypt—the rules of a foreign household, the texture of alien power.

N1 is also where micro‑dreams and fragments appear: brief images, sudden jolts, the sense of falling. Joseph’s first “pit” is exactly that: a falling—the destabilizing threshold experience that initiates the night.

2.3 N2: stabilization under constraint—prison as hidden training

NREM 2 (N2) is longer and more stable, with characteristic rhythms that appear to gate information and protect sleep from waking. Joseph’s prison years function similarly. The dungeon is a constricted environment, but it is also a buffer—an isolation chamber in which the world cannot fully reach him, and in which he develops a new skill: the interpretation of dreams.

In the palace, dreams are anxiety. In prison, dreams are survival. Joseph meets men whose fates hinge on symbols, and he learns to read hidden structure beneath surface images. He becomes an interpreter not only of nocturnal visions, but of human destinies.

2.4 N3: deep restoration—viceroy as slow‑wave governance

At first glance, it may seem odd to map Joseph’s rise to power onto NREM 3 (N3), the deepest and slowest stage. N3 is quiet. Joseph’s rule is busy. Nevertheless, the correspondence becomes plausible if we think of N3 not as inactivity, but as deep order.

Slow‑wave sleep is a period during which the brain performs foundational maintenance and restoration. It is when the hippocampus consolidates short-term memory into long-term memory. Joseph’s viceroy years are N3‑work for a civilization: he synchronizes the economy, stabilizes the future, and creates a structure capable of surviving famine. He consolidates short-term harvests into long-term storage. He becomes the “slow wave” beneath Egypt’s surface agitation—an ordering rhythm that makes survival possible.

Seen this way, Joseph’s role as the viceroy of Egypt maps neatly onto N3: the emergence of deeper coherence in the system.

3. Sleep Stage Transitions as Phase Transitions

Dynamical systems and computational neuroscience increasingly characterize brain states and transitions between them as structured “state spaces,” in which the brain can dwell in one basin of energy (“attractor”) and then switch—sometimes abruptly—into another. Physics offers a language: phase transitions.

3.1 First-order transitions

In a first‑order phase transition, a system can remain stuck in a state even when conditions favor another state; it becomes metastable, resisting change until a disturbance pushes it over a barrier. A first-order phase transition is like flipping a switch: the change happens abruptly, and the system jumps from one state to another with a clear boundary. For example, when water boils, it suddenly changes from liquid to gas at a specific temperature (100 °C (at 1 atm) (at 1 atm)), and this process involves latent heat—energy absorbed without a change in temperature. When ice melts, it suddenly changes from a solid to a liquid at a specific temperature (0 °C (at 1 atm))—again, energy is absorbed without a temperature change.[1]

Imagine the system as a ball sitting in a valley, which represents an energy well—a stable state. In a first-order transition, the ball must jump from one valley to another, separated by a hill. As conditions change (like temperature), the original valley becomes less favorable, but the ball can remain there for a while because it is trapped by the hill. This creates a period of instability, or “metastability,” in which the system resists change even though another state is energetically lower (and therefore more attractive). Eventually, enough energy is supplied to push the ball over the hill, and the transition happens abruptly, releasing or absorbing latent heat. Ice melting into water and liquid water boiling into vapor (at a given pressure) are examples of first-order phase transitions.

3.2 Second-order transitions

A second-order phase transition, by contrast, is more like a dimmer switch: the change is gradual and continuous, without a sharp break or hidden energy cost. Instead of two phases coexisting, the system’s properties smoothly evolve, but certain characteristics—such as heat capacity or magnetic susceptibility—can spike dramatically. A good example is when a material becomes magnetic at the Curie point: the alignment of atoms shifts progressively, and while the change is profound, there’s no sudden jump or latent heat involved. At around 770 °C, iron reaches its Curie temperature, and its ferromagnetic properties disappear.

In a second-order transition, the landscape changes differently: the valley gradually flattens and reshapes into a new valley without a hill in between. There is no barrier to overcome, so the ball moves smoothly as the conditions shift. However, near the critical point, the valley becomes very shallow, meaning the system is highly sensitive to small disturbances—this is where critical fluctuations and instability occur. So, while first-order transitions involve energy barriers and metastable states, second-order transitions involve continuous changes in the energy landscape without abrupt jumps.[2]

Imagine a snow‑covered mountain slope. The snowpack can look stable for weeks, yet it may be metastable—one loud sound or a skier’s weight is enough to trigger an avalanche. Strictly speaking, that avalanche is not a thermodynamic “second‑order phase transition,” but it is a vivid metaphor for tipping‑point dynamics: long periods of apparent calm, a shallowening stability landscape, and sudden release when a threshold is crossed. Other continuous (critical) transitions that physicists study include superconductivity and superfluidity.

In computational neuroscience, sleep‑stage changes are often modeled as transitions between attractor‑like brain states and are sometimes analogized to phase transitions (often characterized as “first‑order‑like”).[3]

Joseph’s life contains metastable moments: heated arguments, moral confrontations, and seemingly small perturbations that precipitate a collapse into a new state. Instability always precedes the descent into another energy well, or into a pit.

3.3 The first descent: the brothers’ argument as critical instability

Before Joseph is cast into the pit, the brothers argue: kill him, spare him, sell him. The family system is “metastable”—tense, unstable, ripe for a jump. A single push changes everything. One moment, Joseph is the favored son; the next, he is in a pit.

In dream language, the pit is not only a location; it is a symbol of the unconscious—the place where narrative dissolves, and identity breaks down. In the language of dynamical systems, a pit is a metaphor for an attractor basin: a low‑energy configuration in which the system can become trapped. Joseph’s descent into confinement is the first‑order transition.

3.4 The second descent: temptation as a metastable ridge

While in Potiphar’s house, Joseph becomes an object of desire for Potiphar’s wife. Every time she sees him, she attempts to seduce him. Joseph consistently rebuffs her advances. They argue; instability emerges. Before Joseph is thrown into prison, Potiphar’s wife presses him: “Lie with me.” Joseph is torn; he almost succumbs to the temptation—the peak of instability. He suddenly sees an image of his father (a dream within a dream). He refuses and flees. That refusal is the ridge of the hill between valleys.

Then the garment is seized. The cloak remains behind like the cast‑off skin of an old self, while Joseph runs into a new state. The system flips: trusted servant becomes accused criminal. Joseph is thrown into a dungeon. Again: abrupt transition into another pit, a low energy state—new basin of attraction.

3.5 Why the garment matters in phase‑transition language

In both descents, the removal of the garment signals that the transition requires shedding identity. As long as Joseph wears the coat of Jacob’s favoritism, he is defined by family optics. As long as he holds his outer status in Potiphar’s house, he is defined by the Egyptian hierarchy. To move into the next state, those definitions must be removed. Similarly, in sleep dynamics, before the brain transitions to the next sleep stage, it must shed the previous state of equilibrium (homeostasis); the previous stage becomes unstable. That is why every transition is preceded by instability.

3.6 The second‑order ascent: from prison to palace

Joseph’s final emergence is different in texture. His ascent from prison to palace does not resemble a descent into the brothers’ pit or Potiphar’s dungeon. It resembles a landscape reshaping itself until the prison is no longer a barrier.

The Chief Cupbearer is released, forgets Joseph, and, two years later, Pharaoh dreams, and the entire system “remembers” the forgotten Hebrew. The delay matters. Joseph is held in a prolonged metastable interval: nothing changes, and yet everything is ready to change. Then, without Joseph pushing, the environment reaches a new critical point, and the old state becomes untenable. The path opens.

In dynamical‑systems terms, this looks less like “jumping a wall” and more like a continuous transition: the old basin flattens until the system slides into a new configuration. Joseph is not yanked upward by force; the world reorganizes around the need for his particular gift. This is a classic second-order transition.

4. Conclusion: Dreaming the Self into Being

Joseph’s story is often read as a tale of fate or providence. That reading is not wrong, but it misses the deeper dynamics. When we overlay the architecture of sleep and the physics of phase transitions, we discover that Joseph’s life is not merely a sequence of fortunate events but a structured passage through states of consciousness and identity.

The recurring pattern of garment-stripping followed by descent into a pit reveals the first-order phase transitions that mark the boundaries between epochs. Each time, Joseph must shed an old order parameter—an old social identity—before the system can settle into a new basin of attraction. The arguments that precede these descents are the metastable ridges, the critical instabilities that tip the system over the barrier. Without instability, there is no transformation.

But the final emergence is different. Joseph does not force his way out of prison: he does not appeal, attempt to escape, or push over a barrier. Instead, the world reorganizes around the need for his gift. The forgotten Hebrew is suddenly remembered because the entire system has reached a critical point where the old configuration is no longer tenable. This is the signature of a second-order transition: no latent heat, no discontinuous jump, but a continuous reshaping of the energy landscape until the path simply opens.

Joseph’s dreams are not only predictions of a future; they are a grammar of transformation. When the old equilibrium begins to wobble—when roles, relationships, and identities become unstable—do not assume you are failing. What feels like a breakdown is often the physics of becoming. Instability is the signature of a new phase trying to be born.

[1] First-order is characterized by a jump in an order parameter (e.g., density) and release of latent heat (entropy/enthalpy changes discontinuously). In the language of thermodynamics, the first derivatives of the free energy (like entropy or volume) are discontinuous.

[2] Second-order (continuous) is characterized by continuous change in the order parameter, but response functions (second derivatives like heat capacity, susceptibility) jumps or diverges; fluctuations and correlation length blow up near the critical point; no latent heat is released.

[3] See Beggs, J. M. & Plenz, D. (2003). Neuronal avalanches in neocortical circuits. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23(35), 11167–11177; Steyn-Ross, M. L., Steyn-Ross, D. A., Sleigh, J. W., Wilson, M.T., Gillies, I.P., & Wright, J.J. (2005). The sleep cycle modelled as a cortical phase transition. Journal of Biological Physics, 31(3–4), 547–569. However, the latest research, including our own, has demonstrated that sleep-stage transitions are more like second-order transitions. See, Priesemann, V., Valderrama, M., Wibral, M., & Le Van Quyen, M. (2013). Neuronal avalanches differ from wakefulness to deep sleep: Evidence from intracranial depth recordings in humans. PLOS Computational Biology, 9(3), e1002985; Passaro, A., and Poltorak, A., (2024) Time-Resolved Neural Oscillations Across Sleep Stages: Associations with Sleep Quality and Aging. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.12.16.628645v3.

Thank you.

All of reality is fractal and the Torah is like a revelation of the Mandelbrot equation that is generating the fractal reality. Since the world was created through the Torah it’s no wonder that the natural and physical world is filled with parallels and fractal impressions of the patterns and processes that fill the Torah — and as consequence also the moral and psychological reality of each person. Thank you for sharing this and being a person who so clearly sees this realtiy that many do not!